|

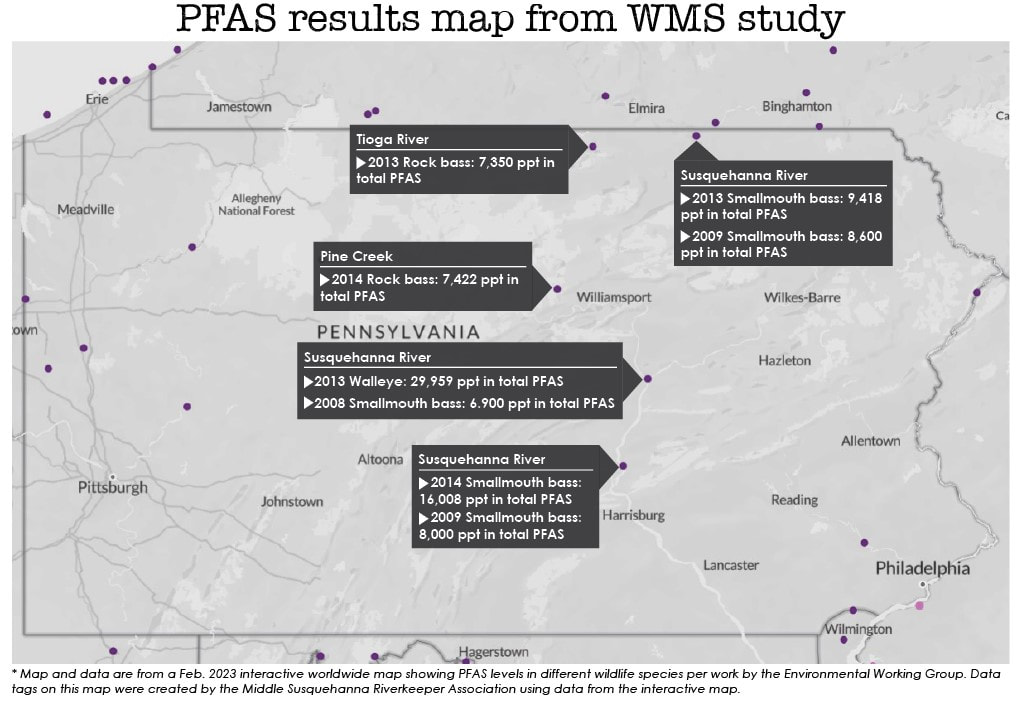

A 2013 sample taken from a walleye fish in the Susquehanna River near Sunbury contained 29,959 parts per trillion (ppt) of combined PFAS – one of the highest concentrations of this emerging contaminant otherwise known as “forever chemicals” in Pennsylvania per a recently released worldwide study featured via an interactive online map. The study, a combined analysis of more than 100 recent peer-reviewed studies, detected more than 120 unique PFAS compounds in more than 330 wildlife species across the world – not just the legacy forever chemicals PFOA and PFOS. “This new analysis shows that when species are tested for PFAS, these chemicals are detected. This is not an exhaustive catalog of all animal studies, but predominantly those published from the past few years,” said David Andrews, Ph.D., senior scientist at EWG. “PFAS pollution is not just a problem for humans. It’s a problem for species across the globe. PFAS are ubiquitous, and this first-of-its-kind map clearly captures the extent to which PFAS have contaminated wildlife around the globe.”

Within the Middle Susquehanna Watershed, which includes all waterways that feed into the North and West branches of the Susquehanna as well as the upper main stem, data from three sites were included on the interactive map. In addition to the 2013 walleye, a 2009 smallmouth bass sample with a 6,900 ppt concentration of PFAS was recorded in the river near Sunbury. A 2014 rock bass with a total PFAS concentration of 7,422 ppt was included from Pine Creek just above where it enters the West Branch of the Susquehanna. On the upper North Branch, due north of Towanda, two samples were included: a 2013 smallmouth bass with a total PFAS concentration of 9,418 ppt and a 2009 smallmouth bass with total PFAS concentration of 8,600 ppt. PFAS are a group of manmade chemicals that all share some sort of fluorinated compound. These per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are widely linked to serious public health and environmental impacts. According to information provided by Michael Parker of the PA Fish and Boat Commission: “PFAS are classified as emerging contaminants because their risks to the environment and human health is not completely understood yet.” In 2018, then-Governor Wolf signed an executive order establishing the PFAS Action Team, and in 2019, PA DEP began sampling drinking water, surface water and fish tissue. “Because there is no federal fish consumption advisory level, PA adopted the Great Lakes Consortium for Fish Consumption Advisories for PFAS, which recommends that for concentrations of 0.05–0.2 parts per million (ppm), people should only eat one meal per month. For concentrations below 0.2 ppm, you should not eat the fish,” according to information from Parker. It is worth noting the conversion in units. The 29,959 ppt found in the walleye near Sunbury would translate to 0.029959 ppm. “Fish tissue sampling sites across the Commonwealth have been chosen based on evidence of high PFAS concentrations in water and in areas where angling is common,” added Parker. “There is currently only one fish consumption advisory in PA for PFOS. It is in the Neshaminy Creek watershed (Montgomery and Bucks Co.). For that entire basin, for all species, do not eat.” On Jan. 14, 2023, Pennsylvania’s Environmental Quality Board announced a new safe drinking water PFAS maximum contaminant level (MCL) rule allowing a maximum concentration of 14 ppt of PFOA and 18 ppt of PFOS (two of the most common forms of PFAS) in the state’s drinking water. The state’s drinking water MCL goal is 8 ppt (PFOA) and 14 ppt (PFOS). Sources and health impacts According to US Geological Survey research fishery biologist Vicki Blazer in an Oct. 2022 report by the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association, the sheer number of PFAS-related compounds can be overwhelming. “There are thousands of these sort of chemicals, which is one of the things that can make them so difficult to get a handle on, understand their effects and locate their sources,” Blazer said. "They’re particularly from point sources such as military bases and airports primarily because the first real public awareness of them was in firefighting foams that have been used on military bases and airports.” Because of the strength of their chemical bond, and because they repel water so well, PFAS have been used in many other things. “They used to be in wrappers that you’d get your Whoppers and other fast food in, although I think that has been phased out. They can be in carpeting and Teflon non-stick pan coating is another big source for people,” said Blazer. “There are many other potential sources, and from such a wide variety of places, they get into our ground and surface water systems, and people can be exposed to them there or even through the food they eat or the air they breathe.” Other known sources for PFAS-related compounds include stain-resistant products, paints, pesticides, certain shampoos and other personal care products, photography products, chemicals used for mining and drilling and various polishes. While much of this research is still ongoing, according to Blazer, PFAS effects have been monitored in labs mostly on rats and mice and aquatically in certain model fish species. “They have shown a wide range of effects, including lipid metabolism, which can be related to obesity. There have also been some neurological effects, some cancers and some developmental impacts,” she said. “Another major effect in humans can be on the immune system. We have found a connection between totals PFAs concentrations and impacts on lymphocytes, which are cells that are associated with producing antibodies – like when you get a vaccine – and are important in killing virally infected cells.” In addition, PFAS in certain testing has been related to hypertension in pregnant women, kidney and testicular cancers, high cholesterol and thyroid disease. Frustrations and next steps While happy to have the results as part of this new interactive map and review that shows PFAS concentrations in species across the world, Matt Wilson, director of Susquehanna University’s Freshwater Research Institute, wishes this data was available sooner. "I think the most remarkable thing about this report is that these data are publicly available, from federally funded projects, and a decade old; yet it took a non-profit putting all the pieces together to sound the alarm,” said Matt Wilson, the director of the Susquehanna University’s Freshwater Research Institute. “It's probably too much to assume we would have collectively taken action had this been published 10 years ago, but I sure wish we had been afforded the opportunity to find out." Figuring out next steps for how to address this emerging contaminant in our watershed can be very complex, according to Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper John Zaktansky. “While raising PFAS awareness and mindfully cutting back on products that contain them is an important next step, there is much more to learn about the scope of these compounds in our local waterways,” he said. “We are part of numerous projects to get a better handle on how PFAS collect within a waterway, including a study out of the University of Florida which is processing a sample of foam collected several months ago on the Penns Creek in Snyder County to see if PFAS are more concentrated in those types of settings. We are anxiously waiting for results for this and other efforts.” Additionally, there is very little known about the interactions PFAS have with other potential contaminants in our river. “In the past few years, I have done research focused on estrogenic compounds, then I did work on Mercury in fish and now it is PFAS. The bottom line is that a fish – or anything in the environment – is exposed to such a complex mixture of various stressors. It can really make it hard to know what individual chemical effects may be,” she said. “I think it is important that people recognize that because one of the things we are questioning now with PFAS is their interactions with some of the things we know are already in those fish. How are those contaminants interacting with each other?” Check out the press release concerning the EWG worldwide wildlife PFAS study here. For the full worldwide map of PFAS concentrations in different species, click here. Click here to check out a report from the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association from Oct. 2022, outlining results from a nationwide PFAS study by the Waterkeeper Alliance.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed