|

Averaging just an inch in length and four grams in weight, the spring peeper’s annual heralding of the spring season depends much more on sound than sight.

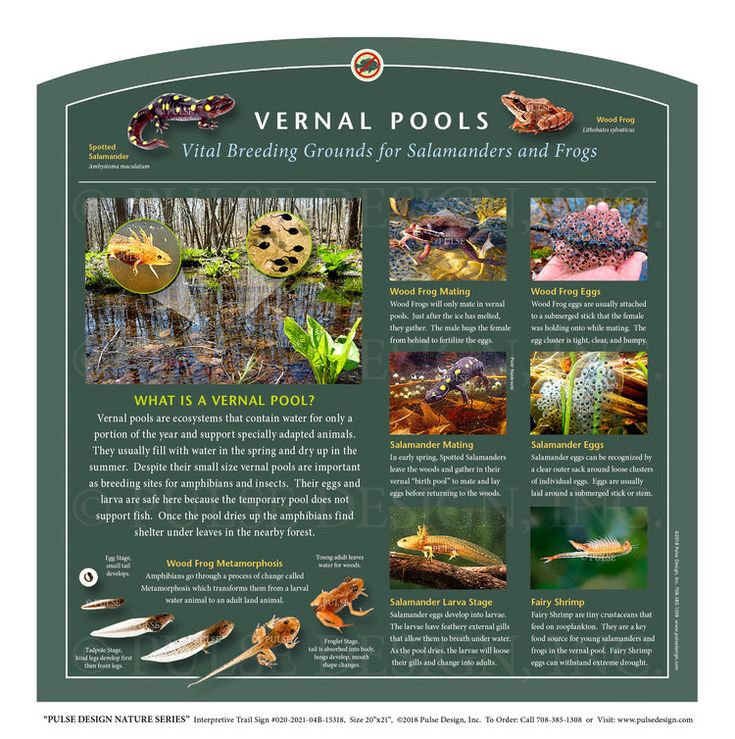

“For such a tiny tree frog, their high-pitched voices can carry up to a half-mile,” said Jon Beam, a master naturalist and outdoor educator at the Montour Preserve and vice president of the Montour Area Recreation Commission. Not only does their call provide an important seasonal rite of passage, but also a distinct audio reminder of the importance of vernal pools within our local ecosystems. “The word ‘vernal’ refers to spring, and these pools are typically a springtime phenomenon,” said Beam. “They typically form where snowmelt – or a combination of rain and snowmelt – collect in a depression on the ground and stay there for a temporary period of time. It could be several weeks or maybe several months before a certain pool dries up depending on conditions.” Certain species of frogs, toads and salamanders take advantage of these impromptu pools as critical breeding and egg-laying habitat. While spring peepers, among other species, can use other wetland environments to reproduce, other species rely completely on the presence of vernal pools for their survival. According to the Penn State Extension system, those “indicator” species include the marbled salamander, spotted salamander, Jefferson salamander, blue-spotted salamander, wood frog, Eastern spadefoot, fairy shrimp and clam shrimp. “One of the advantages in using a vernal pool is that there are no predators for the frogs or salamanders or their larvae. These are temporary pools that can’t support fish or other potential predators throughout the year,” said Beam. “Also, because most of the vernal pools are in forested areas, a lot of leaf litter can be found at the bottom of the pools, which makes good cover for frogs and salamanders. In fact, some of them are so well camouflaged even on top of the leaf litter, unless they move, you can’t tell they are there. If something were to threaten them from outside the pool, they can quickly go under the leaves and disappear from sight very easily.” Because many natural vernal pools are shallow and start forming before leaves develop on the overhead trees, the sun warms them very quickly. “The warmer they are, the faster things can hatch and develop,” said Beam. Triggered by spring rains and increasing soil and water temperatures, these amphibians seem to seek out pools with which they have an ingrained familiarity, according to Beam. “They have a fidelity to a specific area where there is a vernal pool. Not a lot is known about where there is a lot of crossover from one pool to another from one year to the next – it can be difficult to track these little guys,” he said. “However, there seems to be a drive for them to return to the vernal pool where they are born.” Which is why it is important to protect vernal pool areas, even after they are used for reproduction. “If there are frogs breeding in the pool or either the egg masses or larva that have hatched from the eggs, destroying a vernal pool would cause them to die. Without water to support them, they would just dry up and die,” Beam said. “By removing a pool after breeding season, the next spring when frogs or toads or salamanders come back and can’t find the pool, they would have to travel farther to a new area and may not survive. Maybe they’d have to cross a road where they could get run over, or predators would pick them off or they just couldn’t find a suitable new place to breed.” Identifying a vernal pool is a good first step in protecting it. “You want to look for a shallow depression that holds water in the springtime. By summer, you likely wouldn’t realize it was there because it would lack water unless it was an unusually wet summer,” he said. “If you find a shallow pool with salamanders or frogs around it – or egg masses specifically this time of year – that would be a good indicator. If it has fish in it or excessive vegetation growing out of it, the feature likely isn’t a vernal pool.” Wood frogs typically are the first amphibian to seek out the vernal pools, followed by spring peepers and eventually American toads. Once the creature mates and lays its eggs, it quickly leaves, according to Beam. “They don’t stick around and watch over their egg masses. Once the young hatch and are able to leave, they are on their own – they are miniature versions of the adults at that time,” he said. “Once of the reasons most frogs and toads produce a lot of eggs in their egg masses is because not all of them will survive to adulthood. If one percent of them survive, that is pretty good.” Beam recently found some unique vernal pools in the Bald Eagle State Forest, teeming with wood frogs and created in a unique way. “They formed when glaciers were north of us. Because it was so cold just south of the glaciers, it caused paraglacial conditions, where there was a tundra-like situation with permafrost freeze and thaw cycles that formed about 20 of these vernal pools in that region,” he said, adding that vernal pools can even form in manmade structures. “There was this old drainage ditch in a field. Not far from that ditch were several natural vernal pools, and over time, this ditch became one, as well,” he said. “It may have been manmade, but it served the purpose.” |

Above is a video taken along a vernal pool. You can hear wood frogs and other species interacting.

Buy a vernal pool signVernal pool awareness sign

$20.00

Vernal pools are important springtime features that are critical for the early life stages for certain species of amphibians. These signs are 18-by-24-inch all-weather cardboard with metal frame that is easy to insert in the ground and sturdy to withstand various springtime weather elements and other factors. Signs need to be picked up in person at our 112 Market Street, Sunbury, PA office. Depending on supplies on hand, additional time may be needed for creation of new signs. We will email you at time of purchase for more details. If you locate a vernal pool, the Penn State Extension system suggests taking the following measures to protect it:

|