|

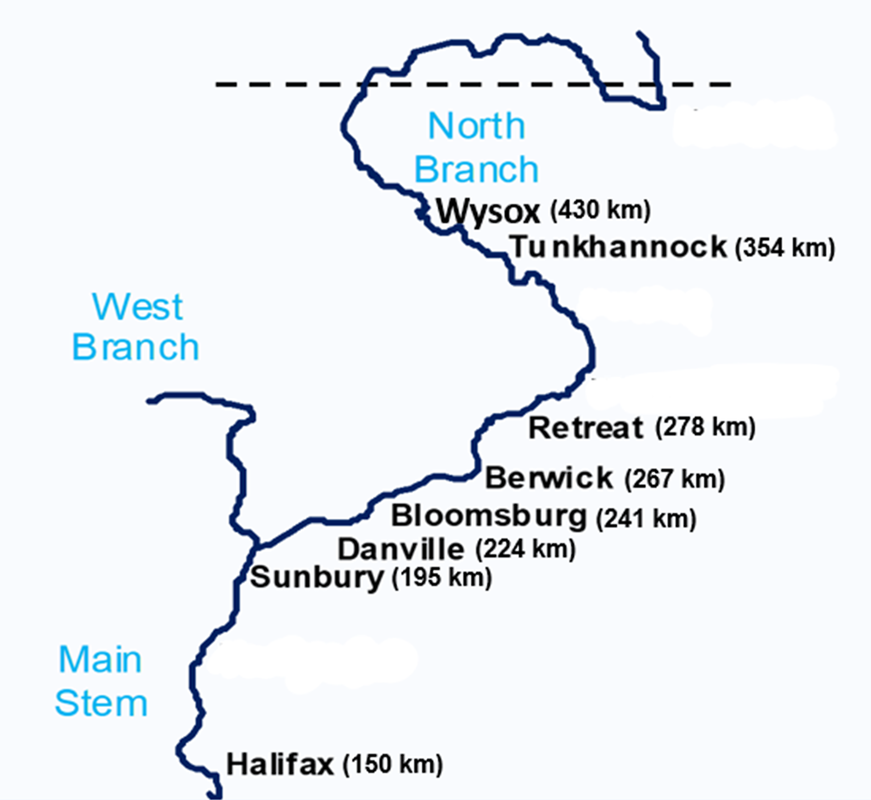

A study from Dr. Brian Mangan and his students at the King's College has found a concerning trend of mercury levels in crayfish and hellgrammite samples collected in the Susquehanna River. “We found mercury in samples at every site we collected at, but the really interesting thing was that there is a significant increasing trend in mercury as you work from lower in the river to the north,” said Mangan. “Our lowest it was about 20 miles north of Harrisburg and we sampled at different locations upriver to almost the New York border.” According to Mangan, the concentrations of mercury double from the lowest sampling site (Halifax) to the site where samples were collected farthest north (Wysox).

“While correlations are, of course, not cause and effect, the evidence suggests mercury is having an effect both on disease resistance and endocrine disruption,” she said.

Macro-focused study Mangan has been monitoring the Susquehanna River for threats for more than four decades – first as an environmental consultant and then, for the past 23 years, via his work at Kings College, where he is the director of the Environmental Program and professor of environmental science and biology. “I have been doing a lot of studies on the river through the years, and a lot of them have been looking at crayfish – primarily to see where the (invasive) rusty crayfish is and how much time it is taking to move from one area to another,” he said. “We realized we could take crayfish and hellgrammites – which are among the largest macroinvertebrates out there for fish such as smallmouth – and analyze them for mercury and figure out what the macroinvertebrate community might be doing in the passing of mercury up the food chain.” Creative collection To help provide the necessary numbers of samples to conduct his study, Mangan and his students built their own custom crayfish traps. “Historically a lot of people have used things like minnow traps, which are football-shaped structures with funnels on each end which you can bait and put in water and they will catch crayfish. A few of my students looked at them and realized they weren’t the best for crayfish. We wanted something that would fit flatter on the river bottom.” Mangan and his team would take 100 of their custom traps to different sampling locations, lay them in lines perpendicular to the shoreline, bait them with cat food, and let them soak for 48 hours. “We’d go back and collect all the traps and the crayfish that might be in them, preserve them and bring them back to the lab for analysis and identification,” he said. “It would vary, but we’d get somewhere between 100 and 1,000 crayfish at some of these locations.” Hellgrammites posed more of a challenge because each had to be collected by hand. “That was pretty time-consuming stuff, but I was pretty lucky during those collections to have a student with me that I’ve since called the ‘hellgrammite whisperer,’” said Mangan. “He would go out and, without even looking, put his hands under a rock and grab one. Then, instead of putting it in a bag or something, he’d actually lift up his ballcap and put it on his head under the ballcap. The hellgrammites would be crawling around up there.” Because of the extra work needed to collect hellgrammites, “We were shooting to to try to get somewhere over the magical statistical number of 30 at each location,” said Mangan. “More if we could get them, because we wanted to make sure that when we did our comparisons of animals between sites, that we were as close to the same size of animal between sites that we could match.” Sample analysis Mangan and his students measured mercury in these samples using a Direct Mercury Analyzer. “It is a great machine because you don’t have to do anything in terms of fancy chemical preparation before analysis,” he said. “You simply have to cut a piece of tissue off the animal and put it in the machine.” According to Mangan, these tissue samples are about the size of an eraser on a pencil. “That means for something like a crayfish or hellgrammite, you have to figure out where on the animal you are going to take the samples from,” he said. “We did analyses of the animals to see where the mercury hot spots may be, but also the more digestible portions of the animals, too, because we were looking for pathways for this mercury to get to fish. You don’t necessarily want the head capsule of a hellgrammite, for example, because it isn’t going to be digested by most fish. We primarily ended up working with sections of the abdomen in both species.” The machine has a tray that can hold up to 40 samples at a time, which allows researchers to load it up and it automatically feeds them one at a time into the machine for analysis. “However, we found out that it can take so long for some of the samples in the end of the tray to get fed into the machine, that the mass of sample could change significantly from the time we originally weighed it and put it into the tray vs. the time it actually gets analyzed. We learned we had to dry all our samples ahead of time to prevent discrepancies.” However, that drying process eliminated the option of assessing live tissue concentrations and had an impact on overall results. “The machine is measuring the amount of mercury in a mass of samples, so because we dry the samples, we artificially impact the concentration,” said Mangan. “It is even more of a twist for crayfish because initially we had to preserve them in alcohol, so we probably caused even a greater loss in things like lipid mass in the samples. “However, the question I was trying to answer was if mercury was present and, if so, were there trends in mercury distribution rather than what’s the concentration vs. some EPA level to determine whether or not to eat the fish.” At its highest, Mangan’s team found 0.2 micrograms of mercury per gram of sample in hellgrammites and nearly 0.7 micrograms per gram in crayfish. Heed the advisories To that end, Mangan added, his study illustrates the importance of fish consumption advisories. “To the anglers, I would say that if you are consuming fish from water bodies across the Commonwealth, pay attention to advisories for where you are catching fish,” he said. “It’s a two-edged sword where you know fish is generally good for us to consume – there’s a lot of good materials in there that you want to eat and take into your body – but at the same time, you have to be cognizant of the fact that there could also be environmental toxins present. “This is especially important if you are in certain groups of people like pregnant women or nursing mothers or young children. You want to pay special attention to these kinds of advisories, not just for mercury, but other contaminants like PCBs (highly carcinogenic chemical compounds, formerly used in industrial and consumer products, whose production was banned in the United States).” You can access the full list of consumption advisories in each watershed of the state at the PA Fish and Boat Commission website. Mindfulness of what you eat from the river is compounded by the unknowns of interactions of things like mercury with other emerging contaminants such as microplastics and PFAS (forever chemicals). “I teach eco-toxicology to undergrads. One of the things I have to confess to them early and often is that most of the toxins that we know anything about we generally know about them only one at a time,” he said. “We need to fully recognize that we and other organisms are moving through a soup of exposure to multiple chemicals all the time.” Research suggests there are interactions between these different compounds – called synergistic effects – but little is known about the dangers of those effects. “In some cases, there can be antagonistic effects where some compounds can actually neutralize or lessen the impact of toxins,” Mangan said. “But, for the most part, we anticipate there are all sorts of crazy interactions taking place. We are flying blind because we don’t know enough about that.” Next steps Mangan is hopeful to extend his research down the food chain to better understand how mercury moves through it – looking at things like mayflies as they can be a primary diet item for crayfish and hellgrammites. He also hopes to do more studies on the advance of the rusty crayfish in the greater Susquehanna River basin. “The Rusty is a much more aggressive beast compared to other (crayfish species). We see that even in handling them in the traps, and their reproductive potential is off the charts,” he said. “One time when we put out 100 traps for a 48-hour soak at one location, we had 1,000 Rusty crayfish in those traps. I have walked to the shore of the river in some places and have watched them swim away in giant waves and clouds. I would hate to be a small macroinvertebrate on the bottom of the Susquehanna with that many Rusty crayfish around. They are altering the system in some of these spots.” Despite the threat of compounds like mercury and invasive species such as the Rusty crayfish, Mangan suggested taking things in perspective. “During my career some of the (positive) changes have been astonishing. We have come a long way from the days that my father used to tell me stories of how nasty the river water was back then while growing up in the Wilkes-Barre area,” said Mangan. “We are not out of the woods yet, but a lot of the gross pollution has certainly been going to the wayside. “The Susquehanna River is crucial to the area – crucial to the economy. It is so good to see people embracing the resource these days vs. shying away from it and it gladdens my heart that the North Branch is going to be River of the Year again to get people out there and interacting with the resource wisely, but still enjoying it for what it is.” For more information, you can contact Dr. Brian Mangan directly via email at [email protected]

4 Comments

Kenneth Maurer

2/7/2023 04:39:36 pm

Inclusion of the current fish consumption advisory for the river around our area would have been nice

Reply

John Zaktansky

2/7/2023 04:50:35 pm

The link is in there to the advisory chart for waterways across the state, including locally. It is live-linked in this paragraph:

Reply

Rachel Hess

2/8/2023 10:24:03 am

Very interesting. Thank you for sharing!

Reply

Don Williams

2/11/2023 01:38:23 am

Great/informative study...thanks for sharing. While at Wilkes College from 1974 through 1978, I collected water samples at bridges over the Susquehanna from Shickshinny to Tunkhannock. I did the field work...someone else did the lab work. It would be interesting to see if the EnviSci team tested for mercury back then and what - if any - changes have occurred over the last 45 years.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed