|

Silky dogwood, buttonbush and elderberry were the most successful species in a recent live stake study conducted by the Chesapeake Conservancy and Susquehanna University. “All three exhibited over a 45 percent survival rate, which is pretty good considering you are simply sticking a stake in the ground and leaving it alone to sprout and grow,” said Matt Wilson, director of Susquehanna University’s Freshwater Research Institute. “None of the other species we studied had better than a 10 percent survival rate.” Live stakes are cuttings off certain trees and shrubs that can be planted directly into the ground and can be very helpful in protecting local streams.

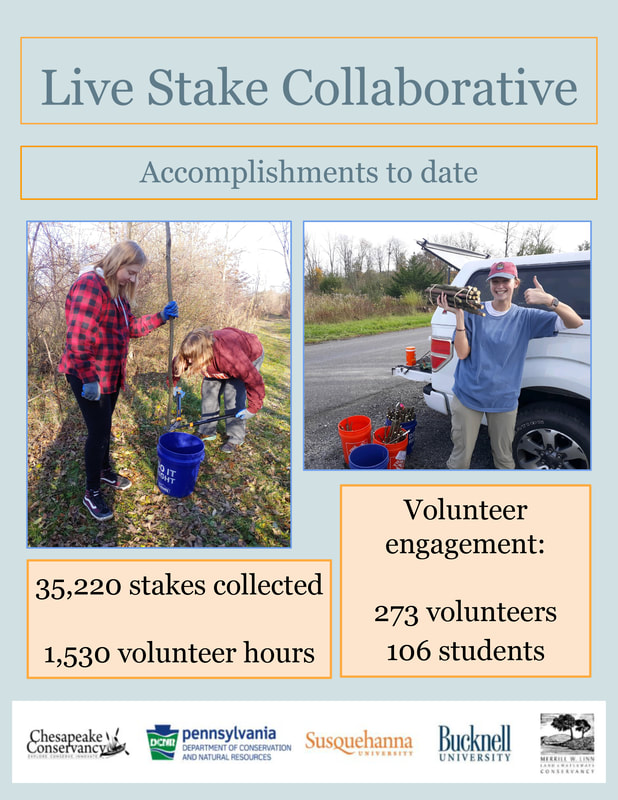

“We blocked those rows four different ways. One block got a herbicide treatment to keep down invasives, another got a rooting hormone, one block had both agents and one block had neither,” said Wilson. “We wanted to determine what works and where money should be invested to make sure these projects are successful.” They found that the rooting hormone and herbicide, for the most part, “didn’t help a whole lot.” “In certain circumstances, they did, like the silky dogwood did a little better with those agents, but none of the other species really did. In fact, some did worse with the rooting hormone,” said Wilson. “We went into it assuming better protection meant better chances for survival, which makes sense, but it really wasn’t the case for this.” They also determined the superiority of silky dogwood, buttonbush and elderberry in terms of live staking success as a species. “The summer of the study was a very hot summer and probably as stressful as you’d encounter for these sort of projects,” said Wilson. “Some of the other species may have done better if things were wetter, but if you want to hedge your bests, these three species seem to survive the best overall.” Data from studies such as this are vital for live stake efforts, Thomas said. “As I am out there running live stake collections, volunteers are always super interested in knowing how live staking works, what the success rates are and if it is worth the work we put into it,” she said. “It is really great to have real info and data to be able to answer those questions and let partners know that stakes will grow where we are putting them.” Volunteers vital The Chesapeake Conservancy’s live stake program, based out of Susquehanna University, serves a six-county region that includes Snyder, Union, Lycoming, Centre, Clinton and Huntingdon counties. “We are just getting into our planting season and are still doing a few more collections of stakes,” said Thomas. “To date for this year, we have 12,500 stakes and more on the way that will be distributed to local partners.” The Live Stake Collaborative includes a group of local partners working together to make the program a success. “It includes organizations like the Chesapeake Conservancy, along with Susquehanna and Bucknell universities which provides us with a lot of our volunteer base – the students are fantastic,” said Thomas. “DCNR helps a lot with educational materials and identifying trees for us. The Merrill Linn Conservancy provides important leadership and a number of easement sites where we are able to collect the stakes.” Collecting stakes typically only requires a pair of loppers or pruners and some knowledge of tree or shrub identification. “There are online tools on how to successfully collect a stake and how to properly identify the best species to collect from,” said Thomas. “It is also important to maintain the correct orientation of the stake. Whatever end is closer to the original plant’s root system is the end you should plant directly down into the soil. Chemicals in the plant help it grow, and if you plant the stake upside down, those chemicals are disoriented and it can take longer for the stake to create roots and lower the overall success rate.” Thomas encourages landowners to do their own live staking projects on stretches of streambanks on their own properties. “If you have a smaller project, you likely can handle it by yourself,” she said. “However, if you have a larger streambank, you can request stakes from the collaborative and we will collect the stakes for you, distribute them to you and can even help plant them if you wanted.” Among its goals with the live staking program, the Chesapeake Conservancy is tackling the state’s growing list of impaired waterways. “Live stakes efforts have been an important part of efforts to successfully delisting impaired streams,” said Thomas. “Hopefully some of the stakes we plant this year will follow along the same path and in a couple of years, we can look back, see all the growth and that our streams are healthier as we keep working to grow the program.” That success hinges on adding more local volunteers to help collect, distribute and plant stakes along impaired waterways. “If you are interested at all in live staking, in volunteering your time or just want to learn more about it all, you can feel free to reach out to me directly,” said Thomas, who can be reached via email at [email protected]. “We have plenty of collecting and planting opportunities coming up, and to keep this program going, volunteers are vital. The Susquehanna River is the largest freshwater source for the Chesapeake Bay, and all the work we are doing up here is definitely super meaningful for everyone who lives downstream.” For more information on the Chesapeake Conservancy's live stake program, including plant ID resources and a video of how to collect stakes, visit www.chesapeakeconservancy.org/precisonconservationinpa/conserve/live-stake-planting

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed