|

A 12-acre orange rectangle is hard to ignore when looking over Google Earth maps of Luzerne County between the towns of Plains and Swoyersville -- the bright iron-hued discharge visibly draining into the North Branch of the Susquehanna River. The location is known as the Plainsville Borehole Discharge, and efforts to clean up the abandoned mine drainage that it produces continue to hit a variety of hurdles, according to Luzerne County Conservation District water specialist John Levitsky.

Today, the Plainsville Borehole Discharge continues to release contaminated water into the 12-acre pool along the Susquehanna.

"The pH is close to neutral at that site, so it doesn't need alkalinity treatment, but the water is very high in both sulfates and iron," said Levitsky. Over the course of the pond, "the iron drops about 80 percent. Coming out of the ground at the borehole, the iron is around 28 to 30 parts per million, and then leaving the basin, it is about five parts per million. Even at that level, you are still able to see that much of an orange stain going down the river." Meanwhile, Levitsky shared that sulfates average around 190 parts per million as the water emerges from the ground. They typically can be released via gas thanks to aeration, however, there is very little aeration within the pond itself, and sulfates are only released where they meet oxygen along the surface. "Very little of it is lost, and the high sulfate level is causing an oxygen deficiency in the Susquehanna River," said Levitsky. Remediation at this site has been difficult, even though Levitsky has a tangible plan he would love to get started. "There's some really good science going on right now with pumping iron sediment into bags that they use for water construction sites. You pump the sediment into the bags and they trap the larger particulate of sediment -- in this case the iron -- and much cleaner water comes out of the bag and could be rolled back into the pond." The process of that release would address the aeration issues that would help release more sulfates, too. "So you are drawing the heaviest of iron sediments from the bottom, putting it in a bag that can be disposed of or reused for some raw material purpose, and then you create a waterfall with the outflow," Levitsky said. "It would then flow into trough, so ultimately, it would create the maximum contact with air so it would aerate the water and increase the dissolved oxygen right where the raw water is coming from, which basically has no dissolved oxygen where it comes out of the ground." In addition, Levitsky is hoping to prove through bench testing that this process can be accelerated and they wouldn't need the entire pond for the remediation -- and perhaps a portion of it could be developed into a community fishing zone. Unfortunately, funding is the main hurdle for this project to proceed -- even beyond the funding it would take to purchase the land from its current owner. "We're looking at about $120,000 in feasibility studies just to figure out if we could do this or not," he said. "Then there is construction, long-term maintenance and disposal. What would we do with the iron. I even asked a scrap yard near the discharge if we could reprocess this back to steel. He laughed at me. He asked how many tons of iron sediment -- I said about 12 tons per day. He responded, 'so like three sticks of steel and then we're done.' It's a huge amount going to the river, but it's a minor amount of you are going to reprocess it back to a metal material." According to Levitsky, programs funded by Chesapeake Bay efforts focus more on nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus along with general sedimentation issues -- a realization he experienced at a Chesapeake Bay/Susquehanna River Basin Commission meeting in Harrisburg that was dominated by discussion on nitrates, phosphates and erosion. "I told them that you'll find no one more interested and agreeable for what you are doing for the Chesapeake Bay, but then I asked why we were all ignoring the orange elephant in the room?" Levitsky recalled. "We have billions of gallons of mine water under the Wyoming Valley where tons upon tons of Anthracite coal was taken out and now it's all replaced with mine water. I am trying to get someone to take samples of nitrogen, phosphorus and suspended solids at this location in an effort to get back on the radar of the Chesapeake Bay program." Levitsky admitted that the Plainsville Borehole Discharge is just one example of abandoned mine issues throughout the region. "If you look downriver you'll see another orange waterway feeding into the Susquehanna," he said. "Solomon's Creek receives 32 million gallons a day of mine water. On average, 12 tons of iron and 42 tons of sulfates a day go to the river from two mine discharges on Solomon's Creek." For more information about the Luzerne County Conservation District's efforts against abandoned mine pollution, visit the group's website: www.luzernecd.org

3 Comments

John McDermott

1/16/2021 05:58:52 am

Maybe the owner could be talked into donating the land?

Reply

2/17/2022 05:58:29 pm

Adding visual stuff like relevant pics/videos could boost the article more and make it interesting for those who are not a fan of reading. Just my 2 cents..

Reply

8/1/2022 03:53:27 pm

I am glad to seek out numerous helpful information here in the put up, we need work out extra strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. .

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

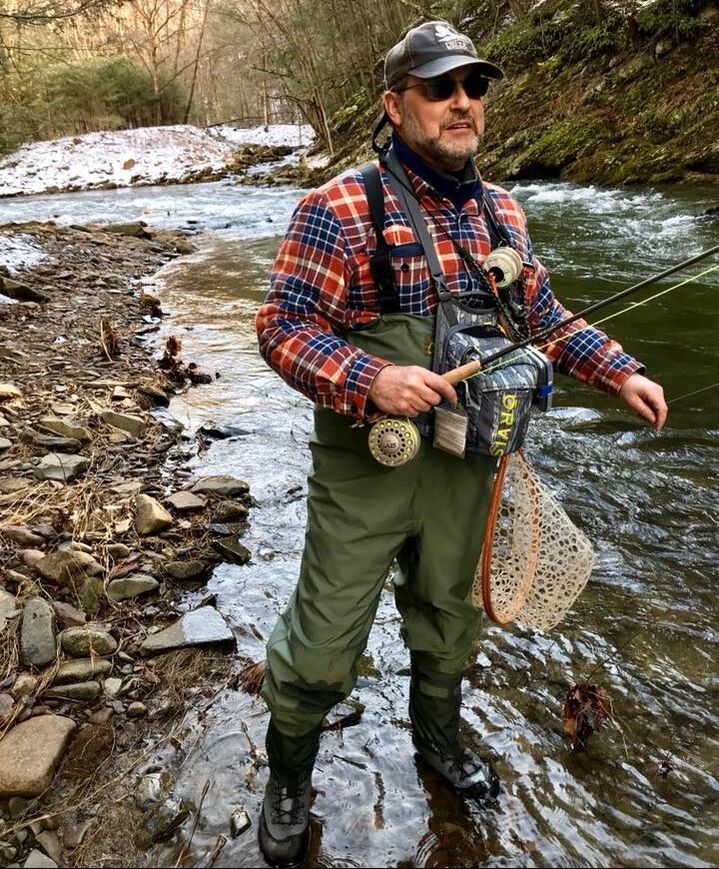

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed