|

Approximately 5,500 miles of Pennsylvania waterways are impacted by abandoned mine drainage issues, according to the Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition of Abandoned Mine Reclamation (EPCAMR). Yet, only a small percentage of them offer the immediate bounce-back potential of the 41.8-mile Catawissa Creek, which flows from underground mine tunnels in the tip of Carbon County through Schuylkill and Columbia counties before entering the North Branch of the Susquehanna River in Catawissa. “The stream itself may be the perfect example of sand and gravel, cobble and boulders – an ideal habitat for fish, microorganisms, benthic macroinvertebrates and all the thing that make up the food web that support the fish that so many people go after,” said Ed Wytovich, president of the Catawissa Creek Restoration Association (CCRA). “It is a drop-dead gorgeous watershed.”

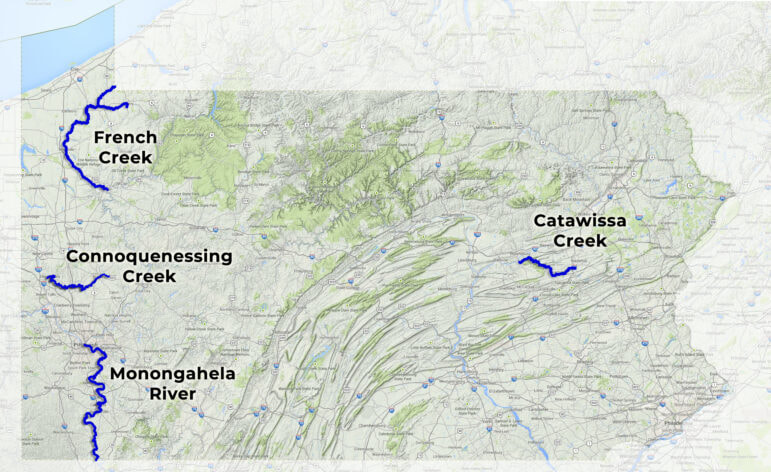

Abandoned tunnels wreak havoc on aquatic life Five mine tunnels which were drilled to dewater mines and reduce the amount of pumping needed by coal miners decades ago, discharges water into Catawissa Creek that – before treatment – is high in acidity and aluminum deposits. “Even though the mines were shut down a long time ago, we are still stuck with what’s left of that era because the tunnels are still open and we have water flowing out of them,” said Wytovich. “In the 1960s and 70s, a study looked specifically at the Audenried tunnel, which runs about three miles from the mines until the water exits. It was found to carry about 80 percent of the acid load that kills, literally, the Catawissa Creek. If we were able to fix the issues coming out of the Audenried tunnel, we would restore 40 miles of stream.” The CCRA, in conjunction with the Schuylkill and Columbia county conservation districts and EPCAMR, have been working to achieve that goal, coordinating successful treatment of two of the other mine tunnel discharges and attempting a similar project on the Audenried in the past. One of those tunnels, Oneida 1, is in the Eagle Rock development near Hazleton. “That discharge has a pH that is normally a little over 4 to 4.5 and carries some aluminum and a negligible amount of iron. We put a project there in 2001 that has six beds of limestone that the mine water is fed through and it comes out with an average pH of 6.5, which is about ideal for brook trout,” said Wytovich. A second mine tunnel, Oneida 3, has also been successfully treated with a passive system. “It consists of a large concrete tank about 120 feet in diameter and 10 feet deep which is filled with limestone,” said Wytovich. “Water is diverted from the tunnel through the system and comes out with a pH around 6.5 and aluminum levels much more reasonable. These two systems are working.” With the Oneida 1 and 3 tunnels treated and negligible impacts from the Catawissa and Green Mountain tunnels, the Audenried is the only discharge standing in the way of the Catawissa Creek reaching its potential. “The discharge averages around 8,500 gallons per minute of water – so it is a good flow. The pH is sometimes down in the high-3s, like a 3.8, to a 4.3 on better days,” said Wytovich. “It is an Anthracite area with a fairly high aluminum content which is toxic to fish and pretty much everything else in the stream.” Efforts to treat the Audenried have historically hit unexpected hurdles. “Initially we had access to limestone sand at a great price and the Army National Guard provided transportation to bring it up. They were very enthusiastic and doing a great job, but due to world events at that time, it just didn’t work out,” said Wytovich. Considering the success at Oneida 1, a similar treatment system on a much larger scale was pursued for Audenried. It included large concrete tanks where water was run through a system of pipes through the limestone to be neutralized and then through a series of settling ponds where the aluminum could settle out before the water was discharged back into the stream. “In the fall of 2005, we got that up and running through a series of grants and it had really good effects. It brought the pH up to between 6 and 6.5 and was precipitating out quite a bit of the aluminum,” said Wytovich. “We had a dedication in the June of 2006, with a lot of people coming out to see what was going on.” Unfortunately, 10 days later, a flood caused massive damage to the system. “It seemed that the mine backed up and blew out and a lot of black water came down. The volume of water was just incredible,” said Wytovich. “It plugged up all the pipes in the bottom of the tanks and plugged up some of the other plumbing and everything turned black from the coal and silt that washed out of the mine.” The team pursued a FEMA grant and eventually worked to get the system back up and running in 2011, but another flood blew out the intake and collapsed the mine opening from where the water discharged. “Thanks to guidance from the Schuylkill County Conservation District and FEMA and PEMA money, we did all the repairs to the best of our ability and put in another type of intake which should be as flood-proof as possible,” said Wytovich. “Unfortunately, issues arose about the rights to enter the property in order to do additional repairs and maintenance, so everything since then has been up in the air. “The good news is that the state is in the process of buying all the land at the headwaters. When that comes to pass, then the Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation has Audenried on a list of projects of streams to get a treatment system that would take care of the Catawissa Creek.” Raising awareness, fighting stereotypes In the meantime, the CCRA and its partners continue to raise awareness and change negative views of the waterway, previously referred to as Sulphur Creek and Black Creek by locals. “The perception is changing now. I haven’t heard either of those names in quite some time,” said Wytovich. “Creeks in the coal region that flowed orange or had a bad smell were called Sulphur creek. Those with coal debris flowing down them were called Black creek. I think it is a great step psychologically that these creeks don’t have to be defined by their previous issues, but there instead is potential there to fix them up and that is what we see in Catawissa Creek – tremendous potential.” To help take additional steps toward achieving that potential, the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association has partnered with the CCRA, EPCAMR, Columbia and Schuylkill county conservation districts to nominate Catawissa Creek as a finalist for the 2022 River of the Year. Voting is open now through 5 p.m. Jan. 14, 2022. You can vote once per email address, so please consider voting as many times as you can. Vote now for the Catawissa Creek by clicking here. “Mark Twain once said that the river has great wisdom and whispers its secrets to the hearts of men,” said “Porcupine” Pat McKinney, the environmental educator for the Schuylkill County Conservation District. “This holds true for the Catty, as its waters speak volumes about the history of the people that have experienced it. From early encampments to the recreational powerhouse it has become, the Catty deserves this recognition.” Nancy Corbin, head of the Columbia County Conservation District, agreed. “This recognition will help the CCRA and its partners continue the good work being done to restore Catawissa Creek’s water quality and create a viable fishery,” said Nancy Corbin, manager of the Columbia County Conservation District. “We look forward to planning fun and educational events to highlight Catawissa Creek restoration efforts, recreational opportunities, notable history and the wonders of the Catawissa Creek watershed for all to enjoy.” Bobby Hughes, executive director of EPCAMR, is excited to promote Catawissa Creek’s restoration so that “future generations will have the chance to see aquatic life, water quality, fishery and recreational opportunities increase and improve. “There are native trout populations and macroinvertebrates throughout the watershed just waiting in the healthier tributaries to make their way to the main stem of the Catawissa once additional water treatment of the historic mine water pollution is addressed,” he said. “I honestly don’t know who is more hopeful and anxious to see this happen: the fish, the bugs or all of our community partners who see the tremendous potential for watershed recovery of the Catawissa Creek.” Some recently shot images of the Catawissa Creek showing a variety of the cool features that make it unique. Images compliments of Columbia County Conservation District's Aaron Eldred, ECAMR's Bobby Hughes and Steve Cornia and CCRA's Ed Wytovich. The Catawissa Creek is one of four Pennsylvania waterways set as finalists for the 2022 River of the Year, and the only finalist in the eastern part of the state:

3 Comments

11/30/2021 08:03:05 am

I vote for Catawissa Creek as the river of the year.

Reply

Tracy Miller

12/2/2021 09:24:36 am

If ever a waterway deserves this honor it is beautiful Catawissa Creek.

Reply

John Zaktansky

12/2/2021 09:36:46 am

Thanks, Tracy. We agree. Please share out the official voting link to your friends and families. We are in the lead, but it is a very close vote with more than a month of voting to go yet. The official voting link is: https://pawatersheds.org/vote-for-a-2022-river-of-the-year/

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed