|

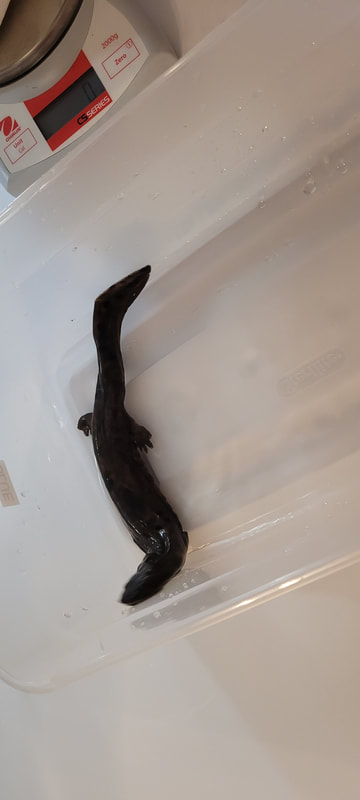

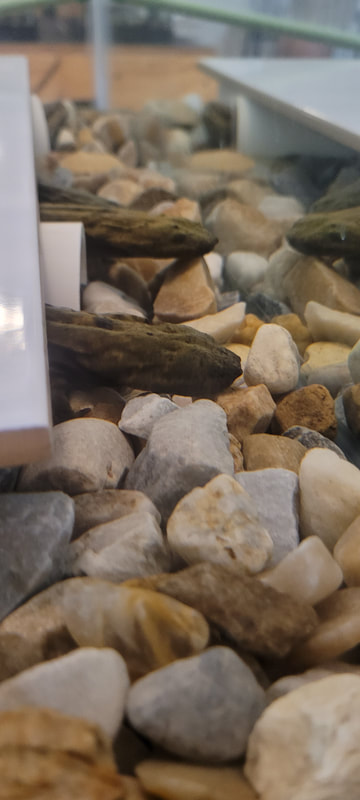

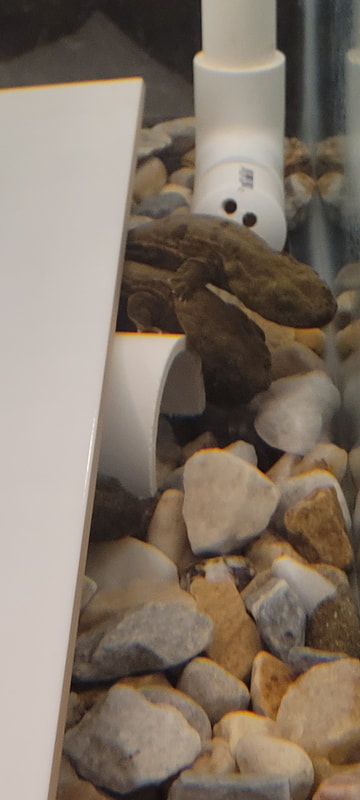

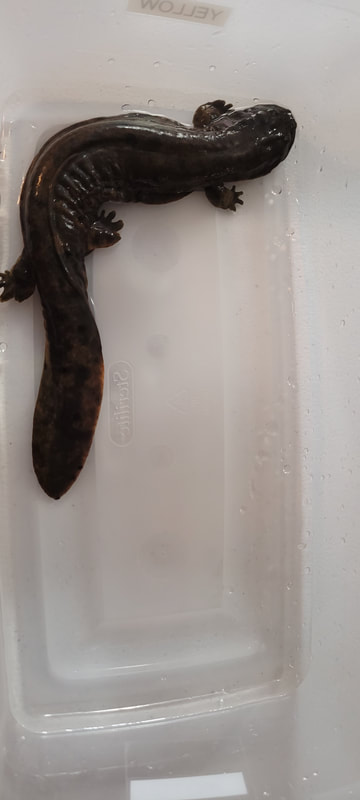

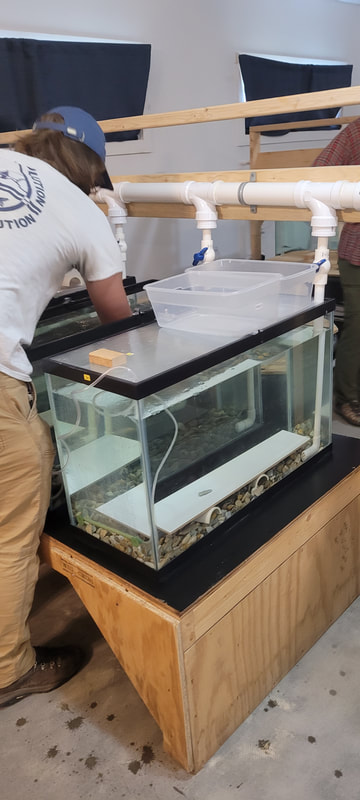

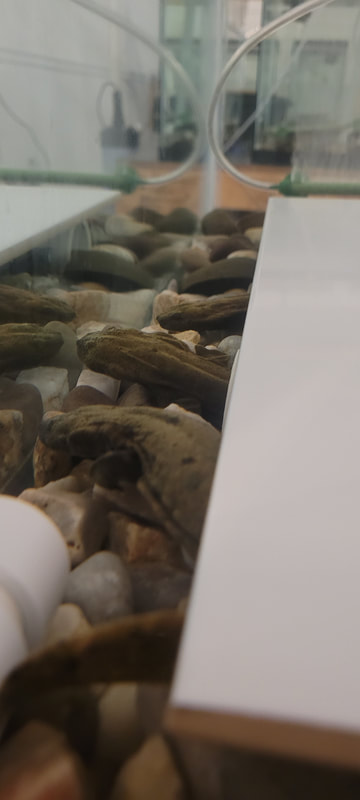

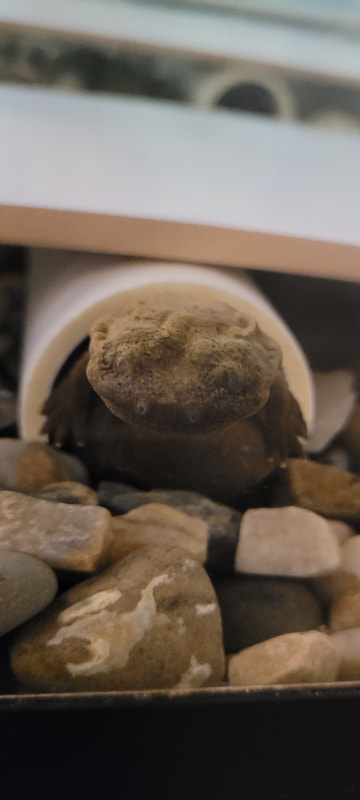

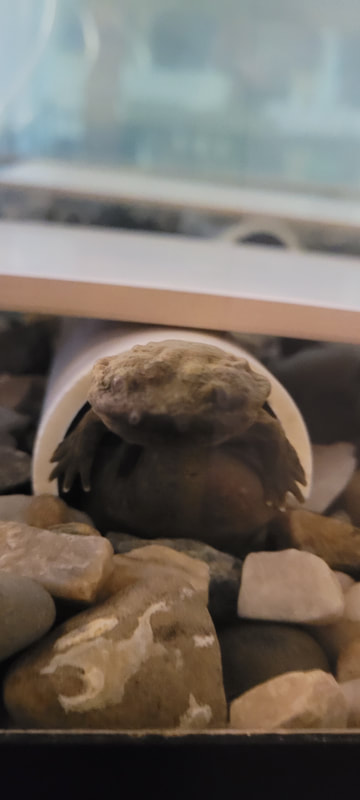

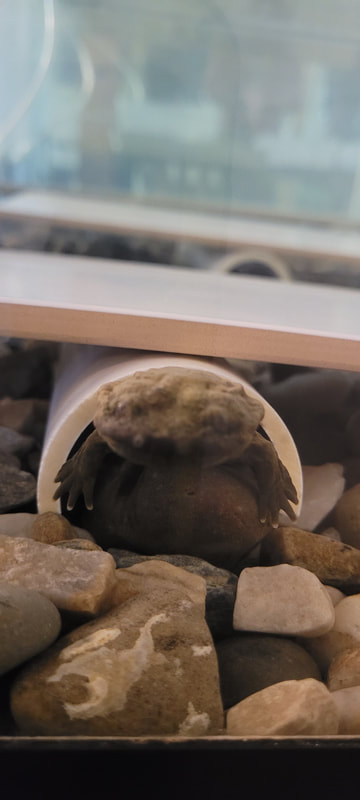

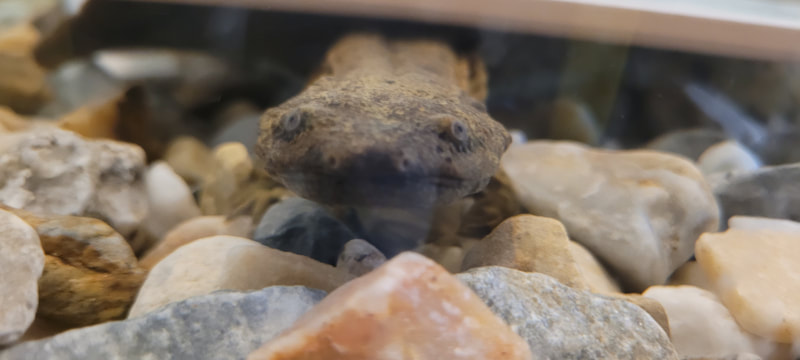

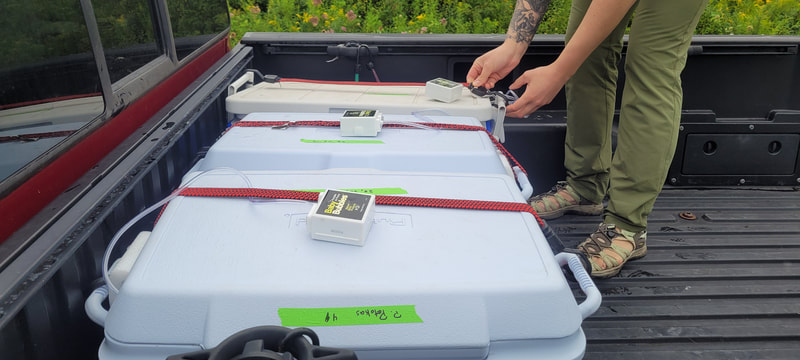

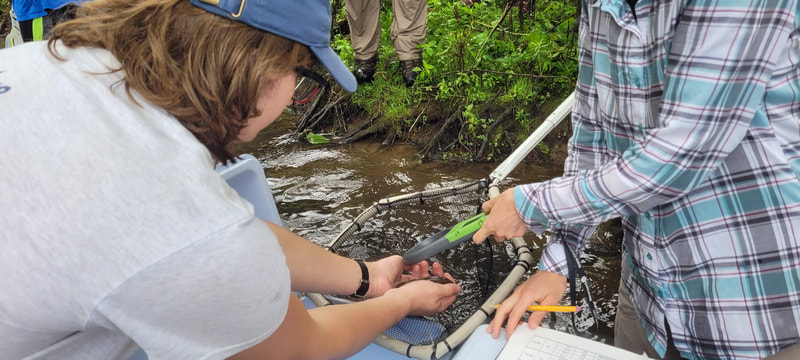

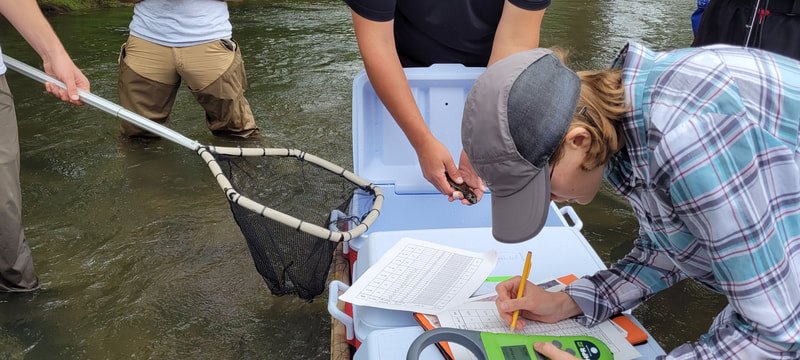

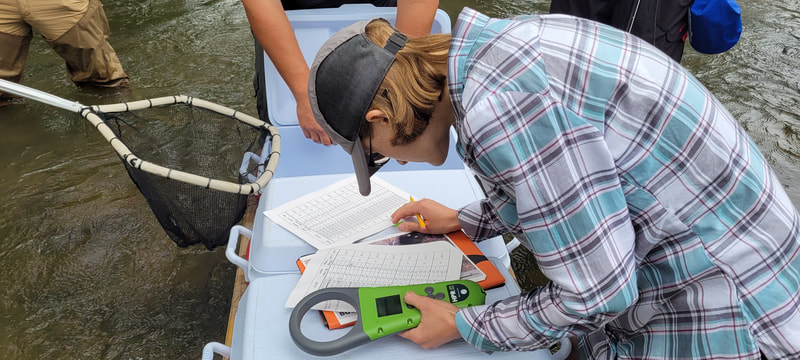

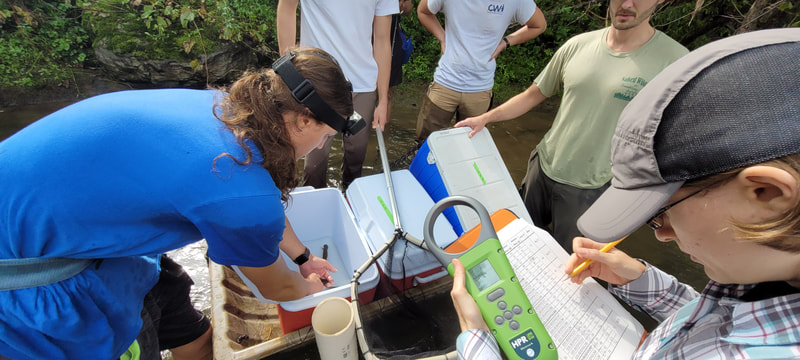

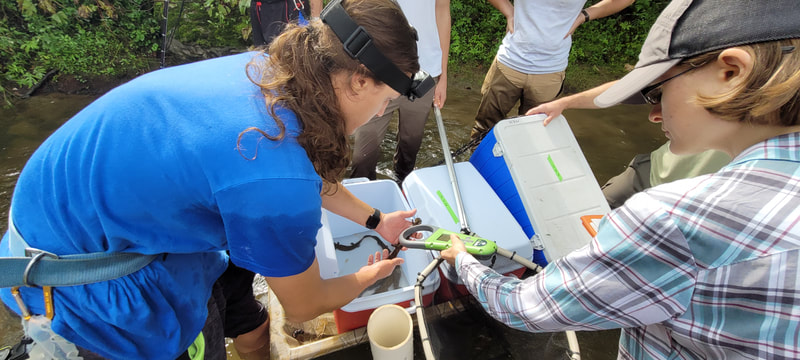

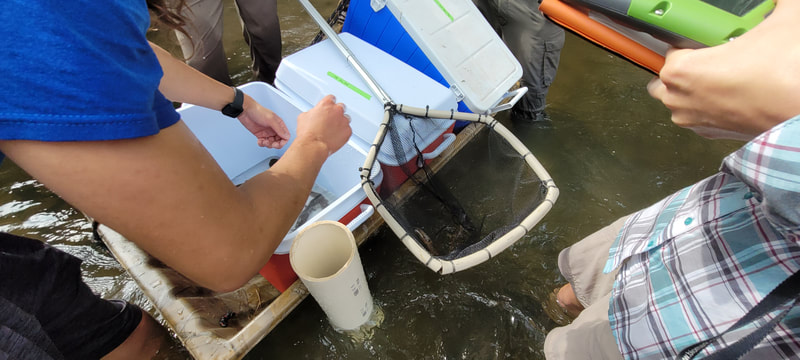

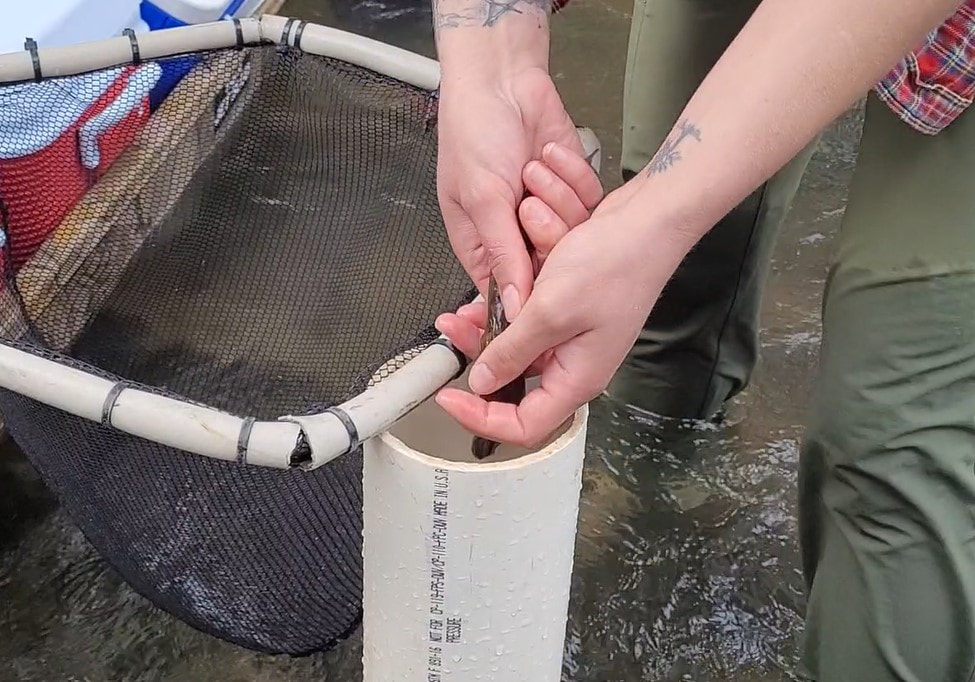

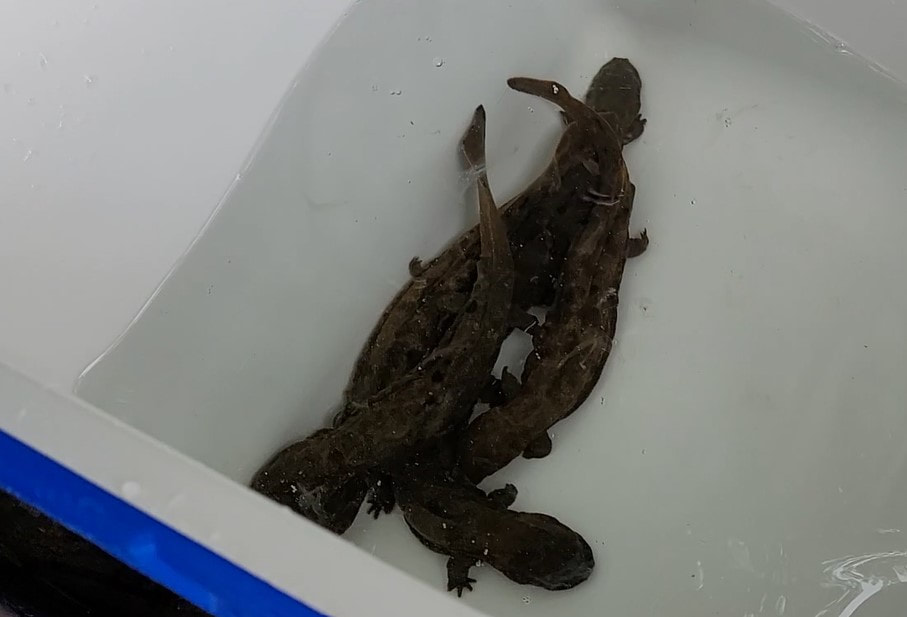

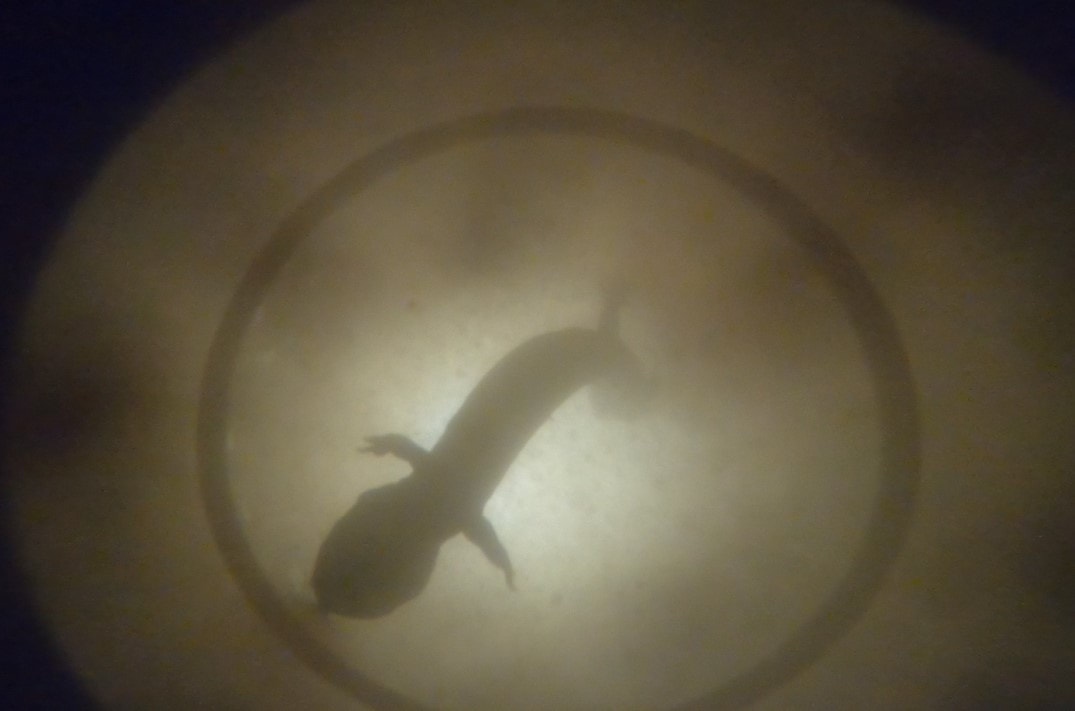

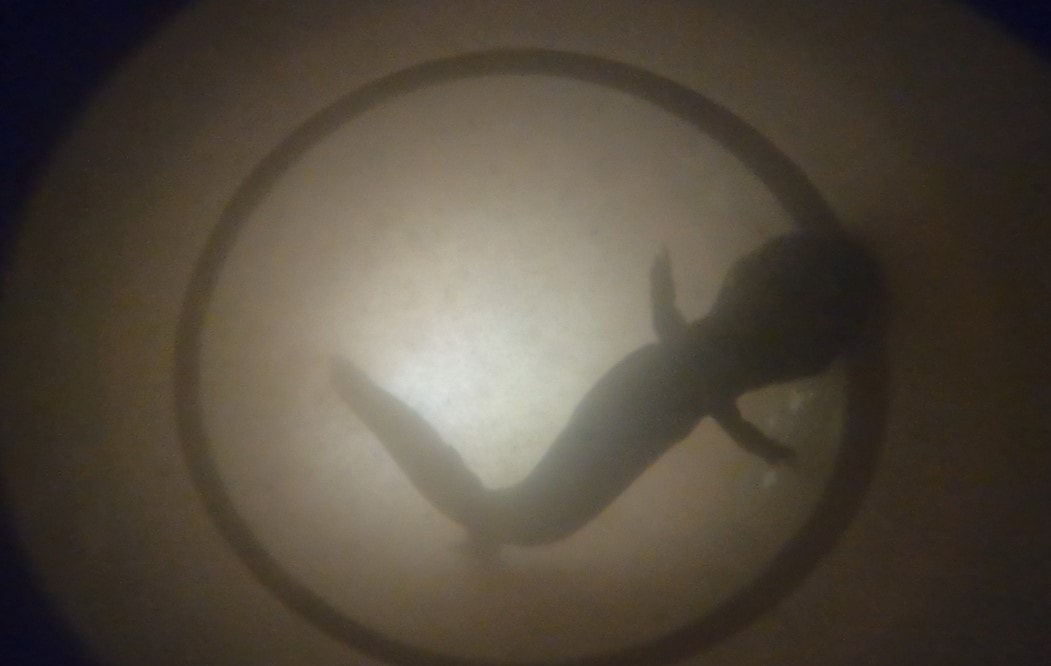

Note: This is the first in a two-part package covering a recent hellbender release as part of a reintroduction pilot program. The second element, a column by Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper John Zaktansky, can be accessed here. More than 10 dozen juvenile Eastern hellbenders were released into a tributary in the upper sections of the Susquehanna River basin on Saturday, Aug. 28, in a groundbreaking pilot program developed by Dr. Peter Petokas, of Lycoming College. "When we started studying the streams in the Susquehanna River watershed, we noticed that hellbenders were either disappearing or gone, so we partnered together to try and restart the species' populations in the upper portions of the region," said Petokas. "It really is a collaboration between Lycoming College in Williamsport, the College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse and the Bronx Zoo, which is part of the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York City.” The effort wrapped up the second leg of a three-part project Petokas hopes sparks additional attention and funding that will allow this program to expand across the watershed. “Back in 2014, we collected some eggs and took them to the Bronx Zoo and they raised them for 2 ½ years, and then we brought them up to a new lab facility for another year. In August 2018, we released 99 three-and-a-half year-old hellbenders,” said Petokas. “Today, we have another group of hellbenders – 124 of them – that were raised by the Bronx Zoo again. We released them back to the wild as a second set of animals to help restart this population. We plan to collect eggs in September and raise them for 3 ½ years and introduce them back to the wild.” The lab, owned by another project partner -- the Wetland Trust -- includes a large meeting area lined with facts and posters about hellbenders on the main level. In the basement, a series of well-maintained tanks lined with PVC structures for hiding housed the juvenile hellbenders. It was here where they were fed a regular diet of crayfish and other species they’d soon be hunting in a nearby creek. The hellbenders were weighed periodically in the lab and identified via RFID PIT tags to track their progress both before and after release – thanks in large part to a solar panel to fuel equipment near the release site. “By collecting these data on the animals, over the years, we can compare how much they have changed and grown,” said Devin Welch, hellbender research assistant at Lycoming College. “All this data helps us to determine the status of the populations which may help in creation of legislation for appropriate protections of the species.” According to Petokas, the biggest challenges to the program usually involve weather and water levels, but getting the necessary permissions for such a project can also be tricky. “Everything we do is under permit from the state of New York so we have to garner support of the state biologists in order to get the permits through. We’ve been very successful in doing that. Through my partnership with James Gibbs and the College of Environmental Science and Forestry, we have the expertise to demonstrate our skills and our success while justifying why we are doing this,” he said. “We need a site that is fairly secure, has good habitat or that which can be enhanced, and offers long-term access for monitoring. Our current site is owned primarily by the Wetland Trust and a couple of property owners who are very supportive of what we are doing.” Currently, the cost of rearing the young hellbenders is shared by the Wildlife Conservation Society and by the Wetland Trust, “but all of the hard work that we do in terms of the physical work is largely volunteerism. Nobody is getting paid to do this, we’re all doing this because we want to see this population restored,” said Petokas. The goal for these three groups of hellbenders released over the course of seven years is to help this population begin on its own. “To produce eggs and young and create a self-sustaining population, but even more than that, we would hope that some of those animals disperse to other areas of the watershed and restart a population on their own,” said Petokas. “That’s our long-term goal – self-sustaining hellbender populations in the upper Susquehanna tributaries.” Using that success, Petokas sees these efforts as a pilot project with a potentially big ripple effect. “We can’t hope to restore the entire Susquehanna watershed with this initial project, but at least we can show that we can do this sort of work here, and maybe we can garner more support and expand the program to more distant part of the watershed,” he said. Why is it so important to protect the Eastern hellbender? “They provide an extremely valuable indication of water quality issues,” said Welch. Petokas agreed, taking it one step further. “They are a good indicator species for water quality, but they are also so unique, being one of only three giant salamanders in the world,” he said. “Populations have been declining dramatically for many, many years and we want to maintain that species as part of our biodiversity. I think they deserve – and have the right – to continue to exist.” To help support Petokas’ reintroduction of Eastern hellbenders to the Susquehanna River basin, contact him directly via email at [email protected]. You can also learn more via Lycoming College's Hellbender Conservation Campaign page. Also, the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association has joined the Center for Biological Diversity, Waterkeeper Alliance, Waterkeepers Chesapeake and Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association in an action against the US Fish and Wildlife Service that hopefully will lead to a threatened or endangered designation for the Eastern hellbender. Follow along with the process on our hellbender page. Here is a video overview and a photo gallery from the hellbender release:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed