Louisiana Waterthrush encounter offers reminder of how citizen science can help crucial species2/21/2024 Riverkeeper's Note: The following column was written by Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association West Branch Regional Director Andrew Bechdel. You can contact him via email at [email protected] Bright wildflower blossoms of spring beauties and purple trilliums speckled the forest floor while the sound of Halls Run trickled beside me as I trekked deep into the woods of the Sproul State Forest one chilly spring morning just a few miles south of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River. Suddenly, a small bird began singing a sweet song from a branch above the creek. The song, a complex composition of three sweet whistles followed by a series of fun jumbled notes, was the bird’s mating call and its proclamation of its right to the streamside territory. It was the song of the Louisiana Waterthrush.

With the forest at my back and the sound of bird song and stream flowing into my ears, it felt as though the natural world was perfect. However, for the Louisiana Waterthrush, survival depends on the presence of forested streams with clean water, a resource that is often taken for granted. The Louisiana Waterthrush is a migratory bird known as a wood warbler, a small and colorful insectivore that primarily lives in forested areas. Most warblers, including the Waterthrush, migrate from the tropical regions to breed in North America, representing the bulk of our colorful bird diversity in the summer months. The Louisiana Warbler arrives to its breeding grounds early, timing its migration with the hatching of the aquatic macroinvertebrates, primarily caddisflies, mayflies and stoneflies, a prey source that is found primarily in healthy streams across the eastern United States. Their specific habitat preferences and diet has made them a visible and audible test of ecosystem health of perennial streams – bioindicators of water quality. Threats past and present The post-industrialized world hasn’t always been kind to the Susquehanna River and its vast network of tributary streams that Louisiana Waterthrush and other stream-dependent species rely on. Pennsylvania’s Forest were extensively logged in the 19th and early 20th century to fuel the Iron Ore industry. This logging or clear cutting resulted in catastrophic erosion, eventually clogging streams altogether. Simultaneously, coal mining emerged in western Pennsylvania, leaving a legacy that still impairs thousands of miles of Pennsylvania’s stream systems. The abandoned coal mines gave water access to underground rock structures that greatly elevated acidity and various heavy metals in discharged water that flowed to nearby streams, killing large sections of aquatic life. In one 2008 study, researchers found that the density of breeding Louisiana Waterthrush was much lower in highly acidic streams affected by AMD in southwestern Pennsylvania. In addition, the breeding success of these birds was lower, and they were less likely to return to the site in multiple years. Thus, the legacy of logging and abandoned mine drainage left in its wake a system of tributaries in the West Branch that were too acidic to support an abundance of high-quality aquatic wildlife. Although the practices of the 19th and 20th century led to the destruction of its habitat, we learned from them. Abandoned Mine Drainage in the West Branch of the Susquehanna River has been mitigated in many areas thanks to water treatment systems that lower acidity and remove heavy metals. Today, Pennsylvania has a thriving second growth forest that cleans our water, and many tributaries of the West Branch that were once too impaired for aquatic life are now thriving again. Unfortunately, in the past decade, new research has suggested that the Louisiana Waterthrush’s habitat may be affected by nearby fracking sites. According to a 2015 study, the Louisiana Waterthrush “accumulated metals associated with the fracking process," finding that within the Marcellus shale region of Pennsylvania, “barium and strontium were found at significantly higher levels in feathers of birds in sites with fracking activity than at sites without fracking." Additional research from this group suggests there is a possible link between the bioaccumulation of barium and strontium and gene expression in Louisiana Waterthrush that may affect “long-term survival and fitness."

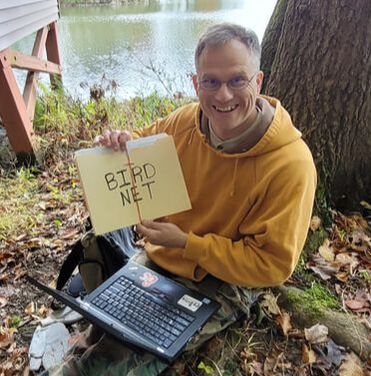

Together, this data helps us paint a clearer picture of the issue, providing us with data that can illuminate us to the long-term population trends of a specific species in an area. Additionally, community-based BioBlitzes have added a new dimension to the citizen science platform, drawing on the strength of community members to rapidly take biological inventories or census of a specific area at a specific time. Bioblitzes can be organized by conservation organizations and scientists but also can be spearheaded by anyone in the community. Real-life examples of how BioBlitzes have improved community ecosystems, specifically pollinator protection, can be found in this September 2022 National Parks and Recreation Association blog post by Michelle White. If you are interested in organizing a Bioblitz in your community but don’t know where to start, you can utilize iNaturalist’s Managing Projects guide to help get started. While Ebird and iNaturalist have become the primary platforms for citizen scientists to record their data, there are citizen science projects that have yet to be dreamt of. One example of such a project is Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Board Member Doug Fessler’s BirdNET project. Fessler, an IT consultant, combined his knowledge of technology and passion for conservation to spearhead the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper’s BirdNET project, a project that received national attention and secured funding for 12 BirdNET units that use sound to detect the presence of specific bird species, such as Louisiana Waterthrush, along waterways to determine if there is any threat to the aquatic ecosystems that they rely on. While the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association took Fessler’s idea and gave it funding and support, it all started with an idea from a person who wasn’t an ornithologist but rather someone with a passion for technology and environmental advocacy. It’s example of how ordinary people can parlay their skills and utilize their passion for wildlife to make a difference and protect our natural resources. Connecting the dots As I continued standing next to the stream observing the feathered trout stab at insects in the stream, another Louisiana Waterthrush began singing its sweet song just a hundred feet away. The foraging waterthrush stopped feeding and flew back up to the streamside perch to proclaim its territory once more. Suddenly, the two birds flew towards each other, and a territory dispute ensued. The two birds met in a mid-air collision, wings fluttered and bills snapped as the other tried to assert their right to the coveted streamside real estate. After a few moments, the first bird settled back down to its original perch and the other retreated to its section of stream. Then, a new waterthrush swooped into the perch, laying up a few inches away. Each bird began scolding the other repeatedly with buzzy chip calls, aggressively flapping their wings towards their opponent, and assertively opening their bills wide enough that I could see their thin tongues and red mouth in detail. After another few moments, the antagonizer fled and resigned itself to staying within the loosely defined boundaries established in the aforementioned dispute. This was the first time I ever witnessed an aggressive territorial dispute between multiple waterthrushes. This prompted numerous questions:

There is only one way to find out – get outside and observe. While not all of us are engaged in research as ornithologists, we all can observe spectacles, such as territory disputes among Louisiana Waterthrush, with our eyes and ears and report our observations. As you start to notice Louisiana Waterthrush in our watershed, we would encourage you to let us know! Email Andrew Bechdel directly with details on where you saw the species and send any photos as well to [email protected] Works cited

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed