|

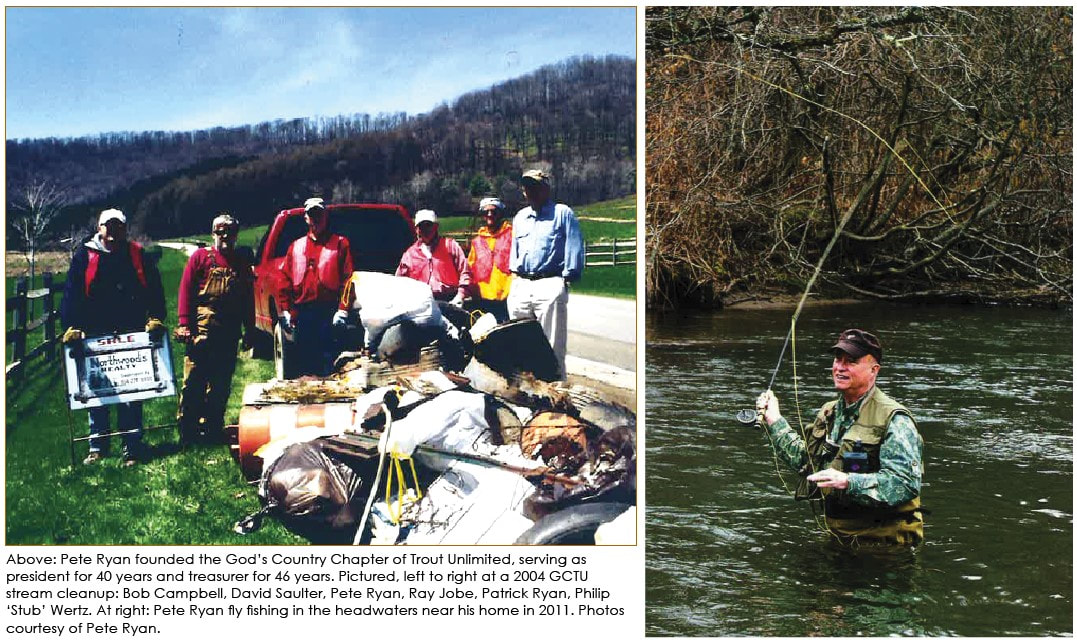

This is the first in what will be a series of stories called Headwater Heroes by Northern Tier Regional Director Emily Shosh showcasing numerous people who have been working hard behind the scenes to improve stream health in the vital yet fragile headwaters region of our watershed. You can contact Emily about this series at [email protected] Our watershed has seen a multitude of challenges and triumphs, but one worrisome, nagging issue of the last few years is engaging and maintaining volunteers. Especially in smaller rural areas where the need for conservation work is ever-present but a large, resource-rich and environmentally engaged population may not be, this issue seems daunting to say the least. Potter County is one of those rural headwater regions. Specific to the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, Potter County is home to the Kettle Creek, Sinnemahoning Creek, Cowanesque River, and West Branch Pine Creek sub basins. Potter County is also the home of Dr. Peter Ryan, who moved to Coudersport in 1976. Following his upbringing in the suburbs of New York City, the rolling hills and streams of "God's Country" quickly became his oasis and the origin of his lifelong love for fly fishing.

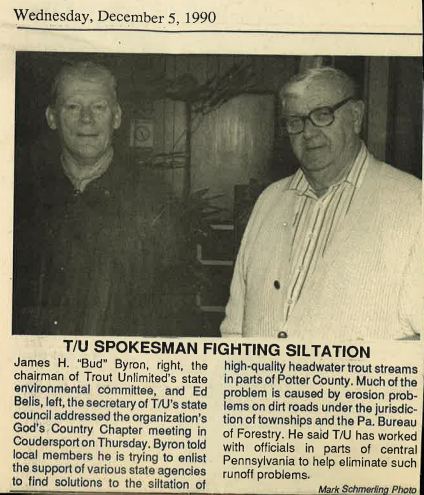

At this time, retired Penn State professor and fellow trout fanatic Ed Bellis created a PA Trout Unlimited-approved scorecard to assess dirt and gravel impacts on streams. Mr. Bellis also deployed volunteer groups and training sessions to complete these surveys across the state. By 1996, these surveys identified 700 hotspots throughout the state, 90 of which were in Potter County. In 1997, the Dirt and Gravel Program was created and took effect across the state, providing funding to each county for dirt road projects aiming to protect streams.

"It was the greatest thing I've ever done with my life," Ryan said, "aside from marrying my wife." These efforts, started from a tiny seed in "The Middle of Nowhere," PA, created a chain reaction that has become a tirelessly effective means to conserve streams and rivers in Pennsylvania. In the last several years, this crew of whistleblowers and boots-on-the-ground advocates has dwindled. Not just in the Northern Tier, but statewide. Watershed associations, Trout Unlimited chapters, and others are folding due to lack of leadership and/or member base. "Perhaps we need to rethink the school-age audience we are attempting to engage, since most end up leaving the area," Ryan surmised. "It is ironic, because most people nowadays seem more aware of environmental issues. But where are they?" A large and diverse body of research has asked the same question. One 2023 study found that the most common self-reported reason to quit environmental volunteering was a fear that advanced age and health problems could be too physically strenuous. Secondary reasoning alluded to lack of time, often from obligations to family and children, or education. Another interesting finding concluded that some respondents quit when simply too much was asked of them, or, volunteering felt too much like a demanding job. Respondents also reported a reason to quit in order to keep up with their actual paid positions and careers. One other study also found that participants became disinterested in the project content/types of projects they were volunteering in. Thus, a solution may come if a diverse collection of opportunities is offered. Conversely, what makes people get started and more importantly, keep going? One study concluded that people begin through a love for being in nature, giving back to the places they love to be in, and wanting to share their knowledge of nature with others. Motivation to be healthier both physically and mentally/emotionally was also reported. Furthering the health benefits concept, one 20-year study reported that among middle-aged respondents active in environmental volunteering, self-reported overall wellbeing was better than those who did not contribute to volunteerism of any kind. Most significant in this study was an estimated 50 percent reduction in the odds of depression or feeling socially isolated through volunteering outdoors. Indeed, the social aspect of environmental work can be very gratifying. Speaking from my own experience, the camaraderie of collaborating with others engaged in conservation work can be awe-inspiring enough to lift anyone’s spirits, conservation-minded or not. Awe-inspiring not simply because such significant work has been done, but because such significant living, adventuring, and memory-making has been done in the process. As a child sits starry eyed listening to the storytelling of their grandparents, I have listened intently to many of Pete Ryan’s fish tales with a fire in my gut. I’ve lived a few fish tales of my own, both solo and in good company. I can breathe easier knowing I gave my best currency - my time - to the wild places that feed my soul. We all worry what our legacy will be. I am blessed to say I know of a certain few who will be remembered for both their adventurous spirit and their dedication to protecting the very places that supply those adventures. "I was afraid we might run out of problems to solve, but they keep coming,” Ryan said. Indeed, although regulations and environmental protections have greatly evolved over the last 50-plus years, so too do environmental problems. "I know people are busy. Work, children and money all influence our day-to-day lives. But if nothing else, people can report observations or concerns. That's all we started doing here at first.” One way to voice concerns for a waterway is the Water Reporter app, which users can upload information to through the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper website. Your riverkeepers can then assess what the culprit may be and which agency to contact. The app is currently under construction until March 31st, and we anxiously await its re-release and upgrades. In order to keep track of volunteering opportunities, we recommend tapping into your local watershed associations, Trout Unlimited Chapters, PA Master Naturalists or Master Watershed Stewards, just to name a few. Even in rural areas, many events are posted via Facebook and Instagram and may be affiliated with a collection of entities as well. The Riverkeeper Regional Directors specifically (Northern Tier and West Branch) are also looking to support these organizations and their planning, events or other endeavors. Additionally, many agencies, clubs, grant programs, regulations, and organizations exist to accomplish necessary conservation work. No matter what skills, resources (or lack thereof), or knowledge - anyone can contribute and communicate with these entities. Like the squeaky wheels of Potter County back in the 90’s, when the right message finds the right audience, change will follow. Sources: Wessel Ganzevoort & Riyan J. G. van den Born (2023, August 7). The everyday reality of nature volunteering: an empirical exploration of reasons to stay and reasons to quit, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. Winch, Kayleigh & Stafford, Richard & Gillingham, Pippa & Thorsen, Einar & Diaz, Anita. (2020, December). Diversifying environmental volunteers by engaging with online communities. Pillemer, K., Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Reid, M. C., & Wells, N. M. (2010, February 19). Environmental volunteering and health outcomes over a 20-year period. The Gerontologist.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed