|

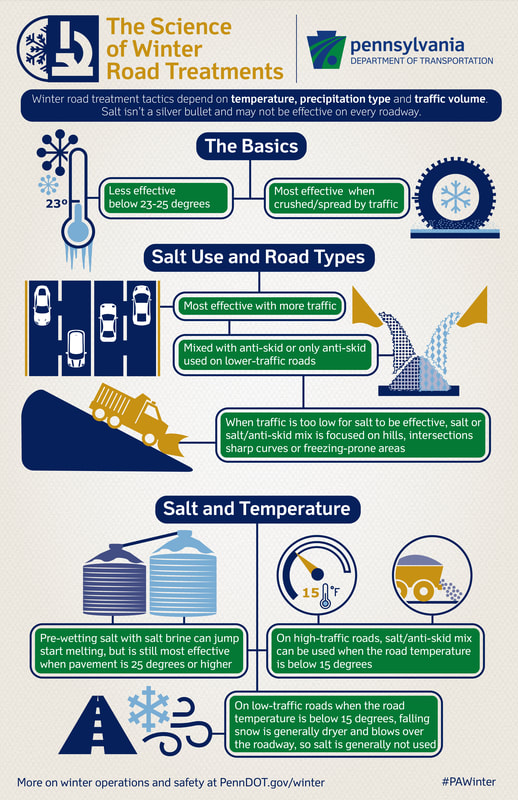

Last winter, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation applied 12.3 million gallons of salt-based brine to the state’s roadways and has spread an average of 807,766 tons of rock salt a year over the last five winters. “They are just one entity that spreads road salt in Pennsylvania, but there is a comparable amount of additional road salt spread by municipal and private entities,” said Ben Lorson, Watershed Analysis Section Chief for the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. “When someone says road salt, you think PennDOT, but it is just one part of a larger problem.” That problem, Lorson added, is closely tied to bigger issue – increased salinization of our freshwater resources across the state.

Aquatic impacts

“The critters that live in freshwater streams are just like us,” said Wilson. “They are much healthier and happier when they drink fresh water instead of salt water.” Impacts in different species depend on their sensitivity to outside contaminants, according to Lorson. “We have seen some chloride concentrations much higher than what we know the tolerance can be for certain aquatic species. Even within those species, there can be a range of tolerance,” he said. “Certain macroinvertebrates and fish are more likely to be impacted first. We know that amphibians can also be very sensitive, as well as mussels.” As salinity increases in streams, “the more sensitive species are affected first, while the more tolerant species persist. “Over time, this causes decreasing diversity within our aquatic communities where you have the highest levels of road salt (contamination).” Salt can have a varying impact on different life cycles within the same species, as eggs and fry can be more susceptible than adults, so species that spawn earlier in the spring can see more of an immediate impact. Increased salinity can also suppress feeding and growth and can be more detrimental if mixed with other external ions or contaminants. Trout specifically is a species of concern when it comes to salinity. Lorson referenced a study out of Maryland where no brook trout were found in waterways that exceeded 280 mg/L of chloride, and could be found in the highest density in streams with chloride below 100 mg/L. In another study he shared – focused on mayfly toxicity in Delaware and Pennsylvania streams – showed that some waterways contained more than 1,000 mg/L of chloride ranging as high as 11,000 mg/L. “It is a general increasing trend over the course of the year. While we may see spikes after winter storm situations, the increasing salinity is not just a seasonal issue,” said Lorson. “Road salt and fertilizers get into the soil and can be released over time and get into the groundwater. So, if we are spreading it today, it could wind up in our waterways years, or even decades, down the road.” Wilson agreed. “Increased salt applications over time have led to build-up in ecosystems so that we even see increased salinity of streams in the summer now,” he said. “This isn’t just a winter problem – it’s becoming a year-round problem that adds additional stress on top of our other impacts from land use and climate change that we have thrown at our streams.” Solutions not simple A change in our road salt usage would require a change in human behavioral trends, according to Lorson. “People feel the need to maintain their daily, normal life during the winter season. To do that, they need safe roads where everyone can drive wherever and whenever they want without concern of someone getting sued,” he said. “Right now, the way we try to maintain that lifestyle is to increase salt usage vs. learning how to slow down and properly drive on snow-covered roads. For any real change, it will take a lot of public education and a shift in behavior.” Wilson agreed that current practices are driven by our “increasingly on-demand culture.” “If we want to be able to drive 100 percent of the time straight through the middle of a storm, then yes, it might be easy to see why we’ve increased salt use,” he said. “But if we give the crews who are working around the clock in treacherous conditions during storms a chance to do their job, be patient and accept that we might need to sit at home for a few hours during those storms – then perhaps we can simply apply less salt to our roads.” Some states have started taking steps to reduce salt usage as they notice decreases in water quality and macroinvertebrate communities, according to Wilson. “Some states have started using porous pavement, which not only decreases ice formation, it actually creates a 77 percent decrease in the need for salt application,” he said, adding that there are other solutions that don’t require a change in infrastructure. “Using a brine solution instead of salt crystals can decrease salt by over 20 percent,” he said. “Other including biodegradable additives to the salt that increase traction and decrease the melting point of ice, making the salt more effective. Some options that have proven effective include adding beet juice or molasses.” When making decisions on how to treat a parking lot, your driveway or a sidewalk in terms of salt use, Lorson suggested mindfully cutting back. “Use as little as possible – just enough to get the melting started,” he said, illustrating it with an example provided by a PennDOT winter maintenance chief used in training for PennDOT staff. “They have three similar-sized blocks of ice. On the first one, they put one shot glass of salt. With the second one, two shot glasses of salt and three on the third one,” said Lorson. “By the end of the training, a couple of hours down the road, they pull out those bottles of frozen water and regardless of how much salt was put on, there was the same amount of melted ice in each container. “It is an example that more salt is not always better. The more salt we put on our roads, driveways, parking lots and sidewalks, the more eventually winds up in our waterways.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed