|

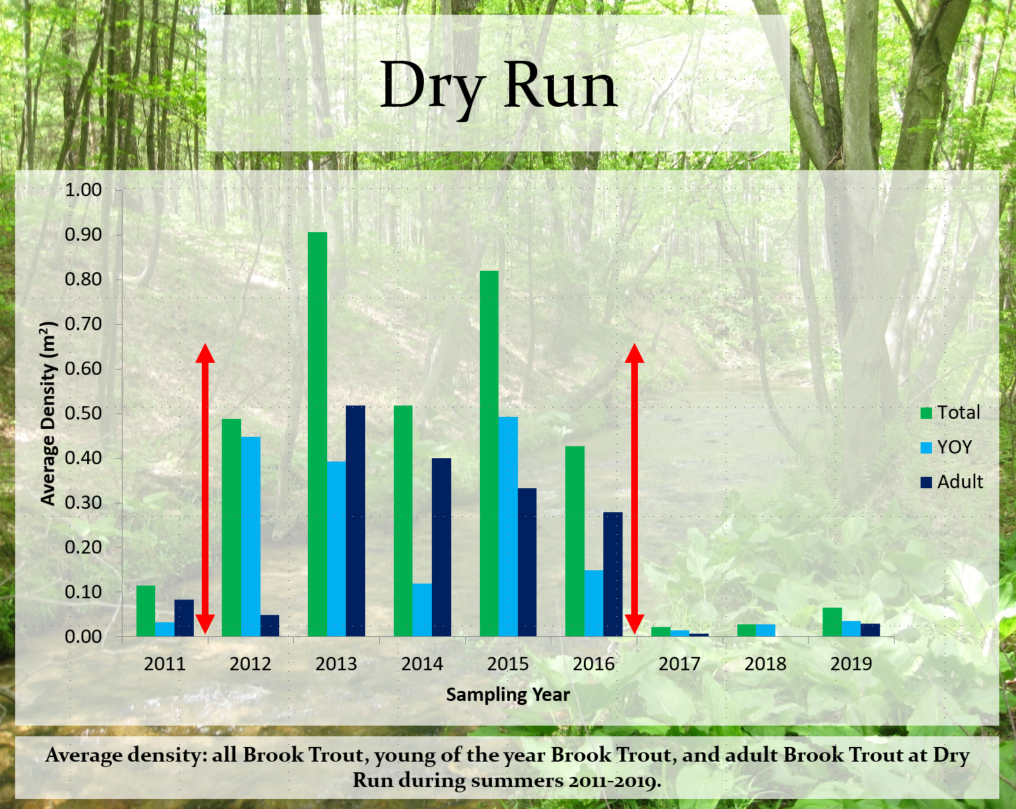

Two high-water incidents along Dry Run at the Hoagland Branch of Elk Creek near Hillsgrove, Pennsylvania, provided drastically different outcomes as recorded via a 10-year study by the Susquehanna University Freshwater Institute. One triggered a drastic increase in young brook trout populations over the following five years – the second marked a stark drop in brook trout numbers. The difference in the two flooding events was timing – one of many variables that dictate how impactful a high-water situation can be to the aquatic ecosystems along the network of tributaries within a watershed according to Susquehanna University’s Jon Niles and Matt Wilson.

“One interesting thing in the timing is that a lot of fish were in their wintering state. They had found their winter habitat, they found food, they put on as much weight as possible. If they had to spend excess energy fighting current and reacting to a high-water event like that, it very well could have an impact down the road – they may not have enough resources stored up for what they need later in the winter season.”

Plus, not every fish species lays eggs at the same times of the year. “Whether they lay their eggs in the winter, spring, fall or whatever, the impact of a high-water event can depend on the life history of the fish,” said Wilson. Thankfully, fish spawning cycles have evolved over time to offset typical high-water concerns, according to Bob Lorantas, of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. “Of the eggs in incubation right now, they are typically in trout streams that are higher in location within the watershed where flows may be less dramatic than further downstream,” he said. Other species that can be found in warmer water sections of the watershed, such as black bass, nest in mid-April to mid-June. “If we experience a high-water event in May, it can dislodge their eggs and cause the fry to be damaged physically, but many times, by that part of the year, high-water events are rarer.” Many species have found ways to adapt to handle unexpected water flow situations. “Freshwater mussels, which slow in metabolism in the winter months, can feel a disturbance coming and they burrow into the stream bed,” said Wilson. “However, if they are stuck in an area with lots of bedrock, or sedimentation issues have impacted the spaces between rocks, it can cause issues.” The health of a waterway – and the banks that contain it – is another variable in determining how a flood event impacts the ecosystem. “In a river connected to its flood plain, fish have backwater areas to hide. Bugs and such can burrow into the substrate,” Wilson said. “But if you have a more channelized situation, something like along the flood wall in Sunbury, there is no opportunity for water to escape and the sheer stress of the water against the wall give fish much less opportunity to hide.” In some of the headwaters of places like the Loyalsock Creek, where there is floodplain, the brook trout can move into those areas and weather the high-water event. “Fish find refuge maybe behind certain rocks or under logs, but where we see steep valleys, there is no where to go,” said Niles. “It is like the log flume at Knoebels, where everything is going down the channel with no where else to go and it can be hard for fish that are fighting to hold their positions to find refuge and escape the need to use extra energy they have stored up for the season.” While fish can also use tributaries as temporary refuges from the raging rapids of a flood-swollen river, Lorantas has yet to find indicators that high-water events regularly causes large-scale fish relocation. “Fully studying a specific event can be difficult because high-water situations can be very unpredictable when it comes to tagging fish ahead of time and tracking their locations,” he said. “I have not seen evidence where fish are substantially displaced or abundance diminished at an original location or increased at a calmer pool downstream on a more permanent basis. To me, that suggests that fish continue to find ways – on average – to tolerate, recover from or move back to their original home ranges effectively.” Another impact of high-water events includes the potential of increased sedimentation washing into waterways from unprotected banks. “Fish don’t like sandpaper run through their gills,” said Wilson. “They are already stressed during one of those events, swimming around trying to find a new place to weather the situation. Sedimentation can be like second-hand smoke or sandblasting without a mask on top of all the other stressors.” The increased sedimentation also impacts species that rely on the bed of the stream for protection and life cycle stages. “Bugs don’t like it because they live down there. For a lot of fish, they come back to a spot to try to lay eggs, but some need certain types of gravel and stones to spawn,” said Wilson. “If there is a big flood and that gravel is covered in sediment, these fish may not be able to spawn correctly or need to work twice as hard to clean the sediment away.” According to Lorantas, when sedimentation results in simply a short-term elevation of suspended materials in the water, fish in general can typically handle that. “Could it cause additional stress and impact a variety of other things? Yes,” he said. “But there has been no real evidence of overt death in those cases.” Niles, however, pointed out that sedimentation is an ongoing issue with longer-lasting potential impacts. “Over a period of time, it can decrease the ability to catch and eat food. Fish are used to dealing with a slightly muddy water, but if it is constantly muddier than normal, it can lead to less feeding, less weight gain and additional concerns,” he said. “As these high-water events take out banks, they release more sediment into a waterway. Additional sediment can lead to changing or moving habitats. Pools can suddenly become riffle habitats, and that impacts each level of the ecosystem. According to Niles and Wilson, global climatic pattern changes may trigger an increase in high-water situations moving forward. “We are in a part of North America that is kind of buffered between the Great Lakes and the ocean, but when it comes to rainfall, we could be seeing lower water flows in August and potential for more major floods in the fall,” said Wilson. “It would be a change in hydrology that for which our critters aren't evolved.” Especially, he added, in terms of the precise biological clocks that many species depend on during their life cycles. “Some species use water temperature to cue when to spawn. Some use light – like so many days after the equinox. Some depend on a combination of both,” said Wilson. “The decoupling of these cues can have a dramatic effect on a number of species. If temperatures get even three or four degrees warmer, there is shifting of the timeline and food availability may not be there for emerging fry,” added Niles. “This would especially be an issue for brook trout and other coldwater species because their current clocks line up with hatches for things like mayflies and stoneflies. But if fish are born a few weeks earlier because of altered biological cues, they may not have anything to eat.” Considering all the variables, it may be impossible at this time to know just how much the recent floods affected our area, especially in knowing how interconnected each part is within the greater aquatic ecosystem. High-water events, at the very least, can highlight the impact we all can have beyond state lines. “It is not a coincidence that every flood ultimately results in a dead zone showing up in the Chesapeake Bay,” said Wilson. “What happens here matters well beyond our region.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed