|

Riverkeeper's note: This is the first in a two-part story package on Superfund sites in our watershed. Check out Riverkeeper John Zaktansky's column on important lessons to learn from these sites by clicking here. While searching online for various permits, rules and applications related to her outdoor guide service, Roambler.com, South Williamsport resident Katie Caputo stumbled across a document about pollution related to a local superfund site she knew nothing about. “I was intrigued by the title, so I began reading,” she said. “The truth is, it felt like I was reading something I wasn’t supposed to find. It also felt like I was reading something I should have already known about.” As she read over the 152-page report about the site and remediation efforts that continue to this day, Caputo was left with numerous questions and concerns.

Based on increasing knowledge of groundwater contamination by volatile organic chemicals, initial tests were done at the WMWA wellfield, and Nicholson and his team noticed elevated concentrations of trichloroethylene (TCE) in some of the wells to the north.

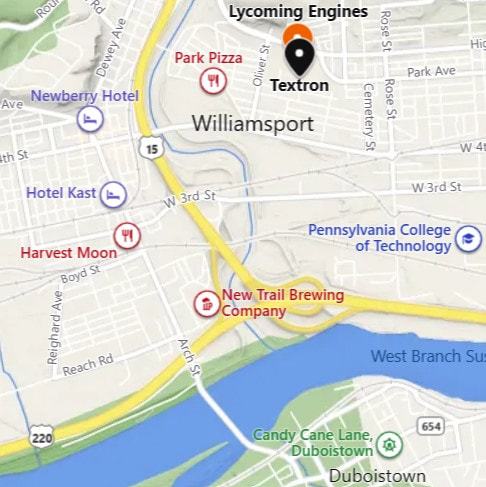

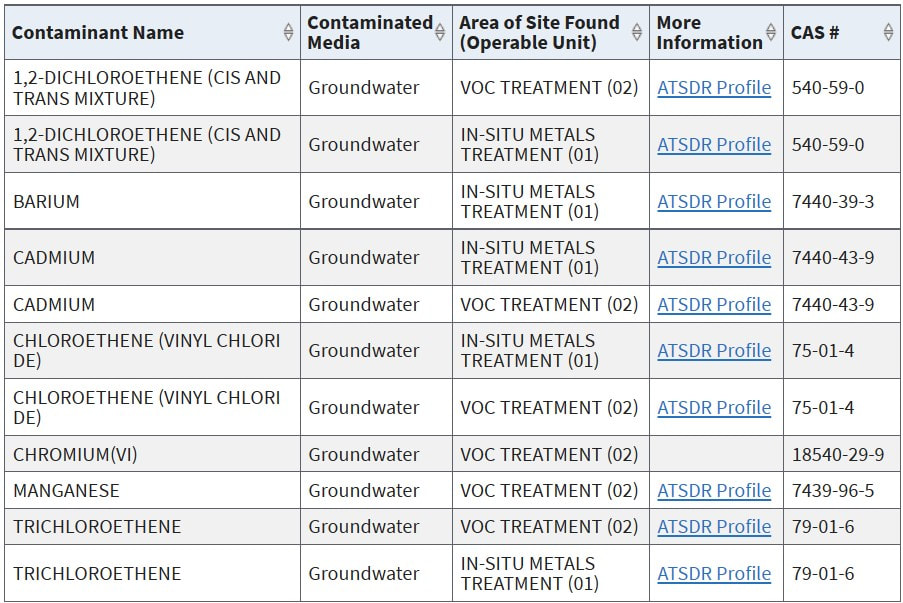

“We started tracking the groundwater contamination north, looking at groundwater relief wells along the levee system,” he said. “TCE concentrations increased as we went north toward Fourth Street, and we realized there was a plume of contamination coming at us.” The Pennsylvania DER (Department of Environmental Resources) – a precursor to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) – traced the contamination from that point to the AVCO Lycoming plant. “As it turned out, there were two different plumes there. One in the shallow aquifer moving south and one in the bedrock aquifer moving to the southwest. We didn’t know any of this as a fact, but TCE could have been dumped on the ground or also put into wells and who knows how long ago that was,” Nicholson said. “It could have been from making aircraft engines for the Korean War or even the second World War. Apparently spent solvents used to clean engine parts could have been dumped there.” According to Randy Farmerie, the DEP Northcentral Region’s Program Manager for Environmental Cleanup and Brownfields, at the AVCO Lycoming site there were “significant levels of chlorinated solvents in the water, over 15,000 parts per billion (ppb) with a maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 5 ppb for trichloroethylene in the 1980s in samples from an on-site well.” According to the EPA report there was also a heavy metals contamination at the AVCO plant location. “Apparently the heavy metal contamination may have been from cadmium and chromium that was used in plating engine parts,” Nicholson said. Groundwater recovery and treatment has been going on as a result of PA DER consent order at the site – now home to Lycoming Engines which is owned by Textron – following discovery of contamination. “The first recovery well was installed in 1985 and treatment systems for the well field to remove contaminants prior to the water being used as the municipal supply have also been in place since 1987,” Farmerie said. “The site was placed on the federal Superfund list in 1990, and since that time, there have been numerous additional soil and groundwater remedial efforts as technology and the knowledge of the site has improved.” What is the Superfund program? In the late 1970s, several toxic waste dumps received national attention when the public learned about the risks to human health and the environment posed by contaminated sites. In response, Congress established the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980. The act, known informally as Superfund, allows the EPA to clean up contaminated sites while forcing parties responsible to perform cleanups or reimburse the government for EPA-led cleanup work. “Sites are scored based on the contaminants present and the risks posed, and based on that score, sites are added to the national priority list (NPL) of Superfund sites, as this site was in 1990,” said Farmerie. “The lead entity with respect to oversight on federal CERCLA Superfund sites is the EPA, with our state DEP participating in all of the work along the way to make sure all of our requirements are met and the citizens of the Commonwealth are protected. “The combined oversight of the agencies provides an extra emphasis and priority to remediate the sites.” The primary goal of the Superfund program, according to David Greaves with the EPA, is to clean up/remediate contamination at these sites to the point where they can be deleted from the NPL. “However, each site is different and the remedial actions to address the issues and recommendations outlined in the five-year review will take some time to observe changes in the contamination in the groundwater,” he added. Each active site gets a five-year review – the fifth such review for the AVCO Lycoming site was released this past September. Striving for improvement According to Farmerie, the groundwater pump and treatment systems continue to operate and significantly have reduced the concentrations in the groundwater plume. “Over 7,000 pounds of chlorinated solvents have been recovered from the groundwater since 2002,” he said. “Groundwater systems have been installed to not just collect the contamination, but also to intercept it before it leaves the site.” While no ongoing risk from the site was found, according to Farmerie, “three off-site residences that may have been impacted by vapor intrusion of contaminants from the plume have had vapor systems installed at their residences.” Nicholson said that he was encouraged by a claim in a recent Pennlive article on the fifth five-year review that they don’t have concerns about contaminants making it to Lycoming Creek. “They must have enough containment up there now near Elm Park that it is able to capture most of it before it gets into Lycoming Creek. However, concentrations of contaminants found in the creek are dependent on creek flow conditions,” he said. “(Back then) we did find some TCE entering Lycoming Creek out there across from the original Little League field at low flow conditions. If it is not affecting the creek anymore, they must be more successful in containing it up there.” According to the recent five-year report, current cleanup/remediation will not be able to return the groundwater in the area of the AVCO facility to an acceptable level for drinking, but this does not pose a threat to human health because everyone within the immediate area of the site is served by the Williamsport Municipal Water Authority. Thoroughly removing contaminants from impaired groundwater is a daunting task, Nicholson added. “One hydrogeologist said it is like taking a sponge in your kitchen sink and saturating it with Dawn dish soap. When you want to get the detergent out, you can’t squeeze the sponge, all you can do is dribble water across it,” he said. “That’s kind of what you are dealing with in groundwater. Contaminated water gets into those matrices of interstitial spaces between rocks and it is very hard to flush that out. Eventually it can work out over time, but it takes a very long time to achieve that.” The Pennlive article refers to several issues outlined in the five-year review and summarized EPA’s recommendations as follows:

Besides the bedrock contamination other issues cited in the EPA report, per the Pennlive article:

“As it pertains to the contamination possibly entering Lycoming Creek, historically this has not been an issue, however, EPA will be working with the PRP (potentially responsible party) to monitor any discharges from remedial systems to ensure that this remains the case,” said Greaves via an email to the Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association. “At this time, we do not see any evidence of groundwater moving beyond the Williamsport Municipal Water Authority, now or in the future.” Greaves added that the EPA will continue to work with the PRP to address improvement needs of the remediation systems running at the site. In terms, any concern of recreating in Lycoming Creek, Greaves responded: “Currently, EPA is not aware of any advisories for recreational and fishing activities.” A better understanding In this case, as with many other Superfund cleanup sites, the pollution predates regulations that made such pollution illegal, Nicholson added. “Either people didn’t know they were causing a problem or thought once stuff was dumped on the ground or down a well, it stayed there forever and didn’t cause issues elsewhere. They didn’t understand groundwater flow,” he said. “There is probably a lot of things around the country that exist that people don’t know about – where wastewater was dumped and people didn’t have any idea of what the future ramifications would be.” That lack of understanding or awareness of a potential major pollution concern in the local community is what Caputo hopes to address in questioning, researching and speaking out about the AVCO Lycoming Superfund site. “More than 30 years have passed since the remedial action plan took effect and the decades seem to have eroded common knowledge of this site,” she said. “I’m planning on attending a Lycoming County Commissioners meeting and offering public comment about this. My goal here is to ensure it isn’t ignored by policymakers and to raise awareness.”

2 Comments

5/25/2023 10:46:20 pm

Dear Middle Susquehanna Riverkeeper,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRiverkeeper John Zaktansky is an award-winning journalist and avid promoter of the outdoors who loves camping, kayaking, fishing and hunting with the family. Archives

July 2024

Topics |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed